This article was reprinted from Nikkei Voice’s March Edition. To help support us subscribe or donate today.

By Frank Moritsugu

The following is my contribution to the Tashme Project—the ongoing collection of remembrances about that particular wartime family detention camp. Naturally the remembrances are being solicited from those who stayed in that camp. So technically I do not qualify—having been a road camper near Revelstoke as was my brother Ken.

But Tashme was where my mother and six siblings had been sent from Vancouver in 1942 to join Dad there. And my remembrance which I am sharing with you has to do with a two-week visit to Tashme in early 1943.

That opportunity came about as the result of a campaign started at our Yard Creek road camp in the Revelstoke-Sicamous chain of men-only camps for Canadian-born and naturalized men.

After being isolated for several months, we asked the authorities to allow us to visit our families. Eventually the authorities agreed, mainly because keeping up our morale would make it easier to control us.

Mind you, the deal was that we were to go visit in groups of only ten at a time from each road camp, and of course, we had to pay our way and any other expenses.

As is well known, one fact that made the Tashme family detention camp quite different was that it was isolated from the other family camps in the B.C. interior. Built near Hope, B.C., just outside the 100-mile “protected area” along the Pacific Coast, Tashme was a considerable distance from the other camps at New Denver, Rosebery, Kaslo, Sandon, Slocan (Bay Farm, Popoff, Lemon Creek), and Greenwood. They were clustered much farther inland in the eastern British Columbia region called the West Kootenays. And there it was possible to visit other camps (after getting permits from the RCMP), and most were built in renovated mining ghost towns where the evacuees got to know some non-Japanese who still resided there.

That isolation of Tashme probably had much to do with the other difference that I discovered on our temporary visit to the camp where our family was.

* * *

So in February 1943, brother Ken and I got on a train near the Yard Creek camp and went back westward to Hope, B.C. There we were trucked the 14 miles to Tashme. We hadn’t seen Dad for close to a year since he was sent to the Yellowhead issei work camp, and I hadn’t seen Mom and the younger brothers and sisters for 11 months. Brother Ken had joined me at Yard Creek later after he turned 18.

Getting to Tashme—to discover what the largest family camp with more than 2,600 residents was like, seeing what the family “home” (the tarpaper shack at 620 Sixth Avenue in the camp) was like, and being able to eat Mom’s cooking again—if temporarily—was great for Ken and me.

And we looked up longtime friends including others from Kitsilano and fellow judoka, several of whom were the camp’s firefighters. Then came the dance that was held at the ranch building which had been converted to the schoolhouse.

Now about my dancing at the time. At the high-school socials in Kitsilano, I could keep the beat of a big-band record but didn’t know one dance step from another. So I stood against the walls a lot.

And also back in Vancouver before the war, most issei parents frowned upon dancing by us nisei lads and lassies. That had to do with the puritanical attitudes the immigrant generation had brought with them from Japan. And they were from a country where physical touching (even shaking hands) was avoided.

Consequently as we nisei reached our teens, we judo students were lectured that dancing with females was not being in true Japanese spirit. Only at the local church were more western behaviour accepted: Our services were in English and we had Junior Church parties at which we even had dancing to pop-song records. But most non-church parents thought it unmannerly.

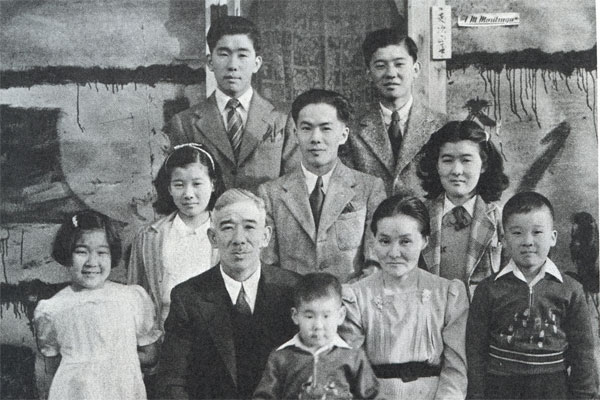

This photo shows the temporary reunion of the Moritsugu family with oldest sons Frank and Ken in February 1943. Taken outside their tarpaper shack at 620 Sixth Avenue are: Ken and Harvey at the rear; then June, Frank and Eileen; then Joyce, father Frank Masaharu Moritsugu, mother Shizuko, and Henry. Ted, the youngest, stands in front between his parents. Photo courtesy: Frank Moritsugu

So much so that in 1940 when the Kitsilano Japanese-Language School graduates association held its annual party on a Saturday at the school, a scandal occurred. We were in one of the classrooms, where the desks and chairs were all moved to the walls, and the attending teens were dancing (or trying to dance) to records being played on a portable gramophone.

Apparently, one issei father in the neighbourhood wondered why one classroom was lit up on that Saturday evening, and came into the school and peeked through the window of the classroom door. Word got around quickly and the next day or so, most of us were lectured directly or indirectly about our supposed carrying-on.

In fact the next year, the graduates association decided to hold the party downtown instead. We went to a new restaurant on Main Street just south of Japantown’s Powell Street. At the New Pier Café, we Kits kids could try to jitterbug to In the Mood on its jukebox without any worries.

Mind you, when news of this escapade spread around, that contributed to the feeling among the elders back home that Powell Street was a scandalous place that young people should be kept away from when without supervision.

As for my dancing, at the Yard Creek road camp, one of our campmates, Tom Uyesugi, had been thoughtful enough to bring a portable gramophone and some great records including those by Artie Shaw. Then in September 1942 I suffered from appendicitis.

After surgery at the Revelstoke hospital, I was recuperating for some weeks. And some days while others were out working, I borrowed Tom’s gramophone and holding Arthur Murray’s how-to-dance book, tried to emulate the steps in the foxtrot diagram on the rough board floor of our bunkhouse while in my pajamas and slippers.

And the following February, there I was in Tashme discovering if my dancing steps would work if a young lady would partner me. One kindly did.

As we danced, I looked up at the high ceiling of the room and saw that the long narrow windows were up along the top of the walls. What’s more, those windows up there were covered with what looked like sheets of old newspapers.

I asked my partner, How come? She said, Oh, some of the nisei climbed up to cover the windows because an old issei man used to climb up outside to check us through those windows. Yup, I thought, just like back home in Kitsilano.

Then when the dance was over, I was walking home another pretty young lady whom I had met briefly years before and who was friends with my sisters in Tashme.

As we walked up the boardwalk alongside the rows of tarpaper shacks heading for her home, suddenly I saw a light flickering and coming towards us. I turned to ask her what that was, but she wasn’t beside me anymore. She had disappeared.

Because we were close to her home, I wasn’t alarmed and trudged along the walk, heading toward the Moritsugu shack about three or four rows away. As the moving light came closer it turned out to be a coal-oil lamp held by an issei man. I said, “Konban wa,” and he grunted and glared at me.

The next day, I found out what had happened.

My young lady had fled when she saw the light coming and gone through the dark space at the back of the shacks to get to her home. She said that in her case—her father being at the Angler internment camp in Ontario (having been one of the men arrested by the Mounties on the day after Pearl Harbor)—at Tashme, it was only her mother, herself and her two sisters. So every time a male was seen knocking at their door, word would get around among the neighbours suggesting all the wrong things.

The man with the lantern was a self-appointed camp guard who regularly checked the camp streets after dark. Not just for possible fires, but also young goings-on.

Even more like back home in Kits, I thought.

But all in all, Ken and I both had a good visit to Tashme. And back at the monastic men-only Yard Creek road camp, we kept happily getting even more letters than before having met old and new friends there.

* * *

More than a half-century later in the 1990s, when I worked with a group of ghost-town teachers in putting together the history, Teaching In Canadian Exile, about the schools in the wartime B.C. family camps, one of them described how she discovered the same difference between Tashme and the other camps farther inland.

Here are some excerpts from what May Inata (later Matsumoto) wrote about her findings after attending the first summer school for teachers (in July-August 1943 at New Denver):

“(In Tashme) being so isolated and confined, we had no inter-relationship with any other community, Japanese or otherwise. And. of course, traveling was prohibited except in cases of extreme emergency.

“Living in a totally Japanese community with its strict code of conduct and ethics, and having very little, if any, contact with Caucasians, I found it not only repressive and inhibiting, but also very demoralizing.

“Then came a wholly new experience in New Denver. On our very first day, we left the Japanese compound where we teachers were housed, to attend the summer school classes at the school in the town proper. . .We had the freedom to go where we pleased. Later, I had the rare pleasure of browsing through the shops in town where we were warmly welcomed.

“During my stay in New Denver and my resulting visits to the Slocan area to the south, which included Bay Farm, Popoff, and Lemon Creek camps, I observed that the evacuee residents there were much more relaxed and receptive than our people in Tashme.”

I remembered reactions like hers were also shared with us at the Yard Creek road camp as campmates who had visited the West Kootenay camps told us on their return how much easier things had been there.

Which reminds me of another Puritanical ruling: it was only at the Tashme camp that the nisei schoolteachers (who were mostly women) were restricted from appearing in public with any male friends.

* * *

Did these differences seriously affect the nisei in the family camps? Happily, not at all. In the postwar years, when freed from our camps, we found opportunities that had never existed for those like us back in prewar British Columbia.

In our new lives we didn’t gather together in Japantowns, big or small, anymore. Which meant that we also lived alongside non-Japanese—at the outset mainly Caucasian. This also led to the issei being replaced by older nisei as community leaders because westernized ways and attitudes grew to dominate.

Among the many huge changes that developed after the war among us Japanese Canadians, what particularly fascinated us nisei was the fact that in new homes such as in Toronto, many issei took up ballroom dancing as well as five-pin bowling.

Some years later in Toronto, we learned to our delight that one judo leader who had back in Vancouver days lectured us against dancing—had taken it up. Not only that, he boasted that he went out foxtrotting and waltzing with his wife regularly to show others how.

How did other Tashmeites make out in this freer world? Just like other nisei—male and female—who grew up in the family and work camps.

They have succeeded in proving that we Japanese Canadians are equal to other Canadians of whatever origin.

And once in a while, better than just equal — to boast in a most un-Japanese way.

07 Mar 2014

07 Mar 2014

Posted by nikkeivoice

Posted by nikkeivoice

2 Comments

[…] does it mean that I thought Tashme sounded Japanese? And did the legislators purposely attach their own names to the camp? As a signifier, the name’s […]

[…] my talk? Yes. If I stay in good shape for the effort. My talk is a survivor’s account of the Japanese Canadian experiences during the Second World War and the postwar resettlement […]