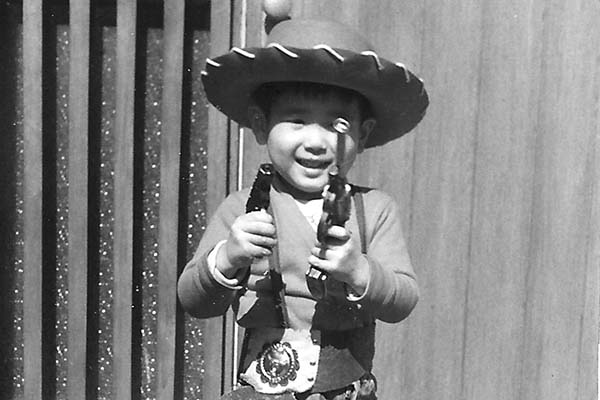

The following is an excerpt from the original introduction to “Being Japanese American,” which has just been released in a newly revised edition by Stone Bridge Press. It was time to update the book, because Nikkei and Asian Americans in general had made great strides in mainstream pop culture in the past decade, and because social media is a product of the last 10 years.Gil Asakawa in Tokyo in the early 1960s, living out his cowboy dreams like any American kid, except he was in the land of the samurai. Photo courtesy: Gil Asakawa

Facebook was just getting started when the book was originally published, and frankly, Asians have found our voice and carved out a significant identity online. The new edition has more text, more photos and more excerpts of surveys with JAs – and Japanese Canadians and mixed-race Japanese.

– Introduction –

I was a banana.

That’s what I’ve been told by people who know—Japanese Americans who’ve been involved in community activism all their lives. Even though I was born in Japan, I haven’t studied my roots in Japanese culture or even the history of Japanese Americans all my life. I didn’t know who Vincent Chin was, or about the No-No Boys. Because I didn’t know about the history, I was told I was a banana: Yellow on the outside, white on the inside.

It’s true that I grew up among Caucasian friends—especially after my family moved to the States—and I wasn’t involved politically or socially with Asians or Asian causes. But I like to think of myself as more than just a fruit. I’m really a dessert. I’m a banana split, with both my “yellow” and “white” sides sharing equal attention.

I know more about Japan than some other Japanese Americans, for one thing. Since I lived there as a kid, I have vivid memories of Japan (albeit the Japan of thirty-five years ago, before the first McDonald’s or KFC stormed the Yamato shores), and feel at home—sort of—when I visit. I’ve also immersed myself in Japanese history and pop culture in recent years, and I feel I’m as much a Japanese as I am an American.

My Japanese-language skills are still pretty wretched, I’ll admit. But that’s not uncommon for Japanese Americans. My mother tried to teach my brother and me to read and write Japanese after our family moved to the States, but we refused. Instead, I learned every American obscenity I could and went around the summer of 1966 proudly enunciating some of the foulest language on Earth, even though my eight-year-old mind had no idea what any of those words meant. My idea of a cool four-letter word wasn’t “kana,” and my vocabulary didn’t include any Japanese alphabets.

Still, I can understand a fair amount of Nihongo, and if I say so myself, my accent on the few words I know is pretty authentic. I’d never “pass” for a Japanese in Japan, but I can surprise an employee in a Japanese restaurant by sounding first-generation, at least on a limited scale. When I’m not cursing loudly in English, anyway.

It’s my appearance that’s more American: rumpled jeans, baggy clothes, loud colors, the loping way I walk (as if I’m moving to the beat of rock music in my head) with my head up and making eye contact with others. And my tastes: brightly painted car, loud music, and colorful language.

Since I didn’t have Asian friends in grade school and high school, I eventually forgot that I was Asian. I thought of myself as white, and I hung around with my white friends and acted like any American kid, at least while I was away from home. I was only reminded of my different face and skin color (why do they call it “yellow” anyway? I’m not yellow…) when racism periodically raised its ugly head and confronted me.

Even while I was attending art school, it didn’t occur to me that I might be a banana—or any ethnic flavor, for that matter. My work followed the paths of centuries of white Eurocentric artists from Leonardo da Vinci to Andy Warhol. I learned about Japanese art, including the ukiyo‑e woodcut prints that influenced the French Impressionists I loved so well, yet I never felt the urge to make “Japanese-inspired” art.

All my life, though, I was Japanese in all sorts of very visible ways—not the least of which was my skin. The banana peel, I guess. I loved all kinds of Japanese food, I usually took off my shoes even in my friends’ homes, I was polite to seniors. I respected authority. Well, sort of.

And slowly, as I got older and began to feel the need to get involved in the community around me, I began to realize that the part of me that was the banana peel wanted to reach below the surface. I wanted to be around others who looked like me (whether or not they were also bananas didn’t matter). I became involved in the local Japanese and Asian Pacific Islander communities, joining non-profit organizations and participating in Asian Pacific American events. These outlets helped me connect my internal and external selves and make sense of my self-image. Ultimately, the interaction with others has helped me accept my split personality and feel comfortable in my own skin.

In a way, I am a born-again Japanese American. I’m aware of both sides of my culture, the inside and the outside of the banana. I am a Nikkei—someone of Japanese descent living outside Japan.

Reprinted from Being Japanese American: A JA Sourcebook for Nikkei, Hapa…& Their Friends, by Gil Asakawa with permission of Stone Bridge Press. Copyright (c) Gil Asakawa 2004, 2015.

Gil Asakawa is a member of the Pacific Citizen Editorial Board, and the author of “Being Japanese American. He blogs about Japanese and Asian American issues on his blog at www.nikkeiview.com, and he’s on Facebook and Twitter. He was recently named the 2014 Asian American Journalists Association AARP Social Media Fellow.

22 Oct 2015

22 Oct 2015

Posted by Gil Asakawa

Posted by Gil Asakawa