Family albums speak volumes about your personal archaeology.

The photos within show everything from family dinners, vacations spend in the sun, and the rose-tinted memory of childhood. However, what if there was a secret album?

Since the 1960’s, Canada has been a hub for immigration around the world, but the image of multiculturalism is somewhat shrouded. It was this that inspired Montreal-born, Brookly and Stockhold-based artist Jacqueline Hoang Nguyen to create an archive.

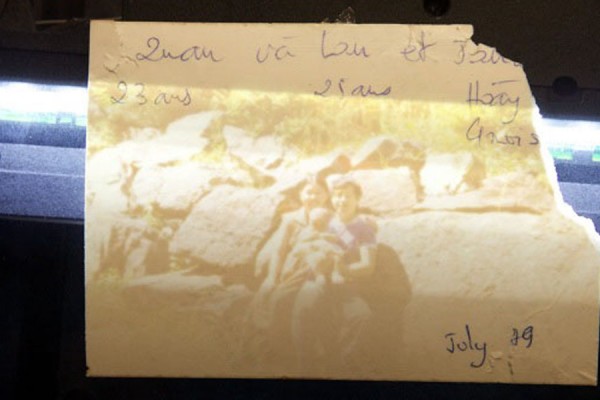

On January 18th, Nguyen, along with a team of volunteers in collaboration with the Gendai Gallery, held a workshop at the Art Gallery of Ontario. The workshop sought out individuals who wanted to share their stories with them through their family albums. Through a process of scanning the photos and arranging them in an online archive, Nguyen hopes to create a snapshot of immigration to Canada in the mid-1960’s onward.

Nikkei Voice had a chance to sit down with her at the workshop to talk about her personal history as an artist and the beginnings of this project.

The Interview

Jacqueline Hoang Nguyen, originally from Montreal, is a research-based artist currently based in Brooklyn, New York and Stockholm, Sweden.

Nikkei Voice: How did your journey as an artist begin?

Jacqueline Hoang Nguyen: I’m a second-generation immigrant, so my parents came here [to Montreal] in the mid 70s in the midst of the Vietnam War. They came with a suitcase and the bare minimum to survive. I didn’t grow up in an environment where I was swimming in a wealth of culture. Basically we had access to television and that was about it. Luckily we had libraries and a bunch of resources, so I frequented there. Otherwise, I studied humanities. It was there that I was hanging out with a number of students who were studying the arts and when I became interested in studying some of the ideas and theories. It led me to change direction and to go into visual arts.

NV: Where did this project come from? How did you get people involved?

JN: Well it stems from a previous project that I completed in 2012 entitled Space, Fiction, and the Achive (Space, Fiction, & the Archive), so in the midst of doing research for that piece, I was doing a lot of research in archives; Library and Archives Canada in Ottawa, and the National Film Board of Canada, Canadian Broadcasting Corporation, and so on and so forth.

I was particularly interested in this legal shift in immigration in 1967 and when the point-based system was implemented and made Canada the instigator of multiculturalism or being known as the country that accepts whoever from wherever.

During the research I couldn’t find any representation of what multiculturalism is supposed to look like specifically from a historical point of view as well when this term was being used more and more in Canada. There’s no trace of it from ’67 onward. Strangely enough there’s no representation on how we are supposed to look at multiculturalism. These thoughts appeared within the making of the previous work and once completed I wanted to undertake these ideas and develop them further, and that’s how The Making of the Archive came about.

NV: Is it difficult for people to talk about their narrative on arriving in the Vietnamese community?

JN: It’s much more a history that is kept silent, at least in my family. My family and my community have a very forward-looking gaze where they are trying not to digest and understand what has happened or revisit the past. I kind of grew up without knowing the history of our family. It’s only much later on that I learned some of my family members died in the boat people journey or incidents that are similar to that.

“it puts the individual in the social context. Somehow being engaged with friends and the environment, and the clothes that they are wearing and the type of activities they were doing talk a bit more about the social fabric than just one’s individual perspective in a diary. It helps to anchor people in the ordinary,” Nguyen said at the scanning workshop on January 18th.

NV: Have you learned a lot about your family history through looking at albums?

JN: A little bit, but there are a lot of gaps. I learned about his [my father’s] point of view of certain things he did, but not many family members who remained behind in Vietnam, and later came to Canada, actually documented their lives. The relationship between class and photography reveals only certain aspects of one’s daily life.

NV: Do you think photographs are more revealing?

JN: Well it puts the individual in the social context. Somehow being engaged with friends and the environment, and the clothes that they are wearing and the type of activities they were doing talk a bit more about the social fabric than just one’s individual. It helps to anchor people in the ordinary.

NV: What is the process like working with people and their family albums?

JN: It’s why we are interested in doing this project in the form of workshops. We get to meet the people and collect their narratives as well. The photographs are accompanied by a story as well to better understand how these photographs come about. This kind of one-on-one meeting is really important during the scanning process.

NV: Is there a hint of nostalgia with participants?

JN: From what I’ve heard so far the kind of narrative that comes back is that they had no idea their parents ‘did this and did that’ particularly realizing that our parents were politically active to some extent. Or that they did certain things that they have never told to us as their children. It’s more discovering certain histories that we were never exposed to. I think that’s the interesting part of understanding the archaeology of one’s family.

NV: What’s the next step in your project?

JN: The first installment of the project is a test site to see how the mechanics are working and if it makes sense. Then we’re hoping to have future installments and we’re in the midst of establishing partnerships with other institutions. The AGO feels like a good venue for attracting people to come as it’s very central and accessible to the general public, but we also might need to consider smaller, cultural centers that are more closely tied to certain communities.

NV: How do you reach out to the older people who have the albums?

JN: So we’re hoping that the kids would convince their parents that this is a good idea. A lot of people are coming with their family or parent’s albums to get them comfortable with the technology and the whole process of it. We’re definitely hoping we can reach the older generations as well. But it’s a question of outreach and being able to gain the trust of certain communities and certain generations as well particularly I know with the Vietnamese community and in my family they are very reluctant to open up about the history. It’s a challenge we need to understand and to overcome. It’s part of a larger social, political moment.

***

This project was also made possible with the help of the Gendai Gallery in Toronto.

23 Jan 2014

23 Jan 2014

Posted by Matthew O'Mara

Posted by Matthew O'Mara