In 1918, Tsune Yatabe volunteered at a Spanish Flu hospital. This photo shows members of the Womens’ Missionary Society at Powell Street Methodist Church, Vancouver, somewhere between 1922 to 1924. Photo courtesy: Shinobu Family Album.

In 1958, the Japanese Canadian Citizens’ Association (JCCA) held a contest inviting Nikkei to contribute essays based on their life experiences. Mrs. Tsune Yatabe (1892-1984) submitted an essay about volunteering at a hospital in Vancouver during the 1918 Spanish flu pandemic. A temporary hospital was organized at Strathcona School on Oct. 19, 1918 to accommodate flu patients of Japanese origin. In 2015, Tsune’s granddaughter discovered her story in the JCCA online archives at Library and Archives Canada.

In 1918, Tsune had two young sons, Mas, 4, and Eiji, 18 months. Her husband, Gensaku Yatabe (1879-1938), ran a gardening business in Vancouver. He would help the hospital by delivering ice for the patients.

Some of the volunteers included in this essay or photos may be familiar to readers, including:

Rev. Yoshimitsu Akagawa (1880-1956) established the Japanese United Church in the Fraser Valley, B.C. His wife, Yasuno, was a trained nurse. They were the main organizers of the hospital at Strathcona School.

Dr. Kozo Shimotakahara (1885-1951) was the first Japanese Canadian physician. Of the four doctors who worked at the hospital (the others were Drs. Sato, Ishiwara and Kinoshita), he was the only one licensed to prescribe medicine.

Mr. Kosaburo Shimizu (1893-1962) became an influential and well-known Japanese United Church minister in B.C. and Ontario. He was ordained in 1926 and appointed pastor of the Vancouver Japanese United Church on Powell Street in 1926, eight years after his volunteer work in the hospital.

Miss Etta DeWolfe (1878-1961) was a Canadian missionary who worked in Japan, and later for the Japanese United Church in Vancouver.

Mr. Tsutae Sato (1891-1983) was the principal of the Vancouver Japanese Language School at the time of the Spanish flu pandemic.

Tsune worked closely with infected patients and became a patient herself in the hospital. Her surviving children and grandchildren, who read her memoir many years later, did not realize how close she had come to death. Several other volunteers at the Strathcona hospital were not so fortunate; in the months after the hospital closed, they became infected and died. One of the Strathcona volunteers lost her infant daughter to the flu at this time.

Tsune had six more children in the 1920s. All were born at home with the aid of Mrs. Tateishi, the midwife in this memoir. Gensaku died a year before the Second World War. The family moved to Ontario in 1942, with the help of one of Gensaku’s clients, and avoided internment in B.C. Tsune wrote this memoir when she was living in Toronto.

The translated memoir was published in the Nikkei Images newsletter in 2016. Kazue Kitamura translated Tsune Yatabe’s story from Japanese to English and Ted Shimizu and Kazuko Yatabe identified some of the people in the photographs. It has been referenced by historians in Canada and Japan recently because of similarities between the current pandemic and the Spanish flu.

This photo shows members of the Womens’ Missionary Society at Powell Street Methodist Church, Vancouver, somewhere between 1922 to 1924. Four of the women had worked at the 1918 Spanish flu hospital based at Strathcona School; Mrs. Shimotakahara was the wife of Dr. Shimotakahara. 1: Mrs. Tsune Yatabe, 2: Mrs. Yasuno Akagawa, 3: Miss Etta DeWolfe, 4: Mrs. Suno Yamazaki, 5: Mrs. Shimotakahara. Others in photograph: Mrs. Sada Shinobu, Mrs. Yataro Arikado, Miss Florence Bird, Mrs. Okada, Mrs. Kato, Mrs. Ohora, Mrs. Niimi, Mrs. Masuda and Mrs. Komiyama. Photo courtesy: Shinobu family album.

The Spanish Flu by Tsune Yatabe

In mid-October of 1918, a terrible influenza epidemic arrived in Canada from the battlefields of World War I in Europe. It was called the Spanish flu. The Spanish flu spread to Vancouver, B.C., where many Japanese immigrants lived. Public schools and churches were forced to close to prevent the flu from spreading. Many patients could not stay in hospitals, as many doctors and nurses had been sent to work at the battlefields.

A Japanese pastor from the Methodist church, Mr. Yoshimitsu Akagawa, and a missionary from his church took the initiative to tackle the epidemic. Mr. Akagawa said, “The first Japanese patient was Akio Iwatsuru. He was a Japanese student and a Christian.”

It was terrible and sad to see so many patients unable to get treatment and dying. Mr. Akagawa visited the Japanese Consulate for some help and advice. He and Mr. Ukita (the Consul) arranged for a special hospital to be set up for Japanese patients. They obtained permission to use Strathcona Public School as a temporary hospital. Many Issei and Nisei had studied in the school. There were four main doctors: Dr. Shimotakahara, Dr. Takahashi, Dr. Ishihara and Dr. Kinoshita. They worked very hard on behalf of their patients.

Fortunately, Mrs. Akagawa was an experienced nurse. She devoted herself to taking care of patients. She worked with Mrs. Nakano, who was married to a pastor, and Mrs. Higashi, who was from the Japanese Red Cross. One of the nurses was the daughter of Dr. Watanabe. Although more and more patients arrived at the hospital, few nurses applied for the work. They feared getting infected. We saw Mr. and Mrs. Akagawa working very hard. As healthy people, we felt we should do something to help them. Although we and other friends from church discussed what we should do, we did not have any good ideas. Some of us said that we should not risk becoming infected. Others said we could help the Akagawas by giving them things they needed without directly contacting the patients.

My husband went to the hospital. He wanted to help the patients, but Mrs. Akagawa said, “We prefer women, not men, as nurses.” The next day, I applied for the work. After learning that I applied, two church friends also applied. I was very glad. One of us worked in the kitchen, and two each worked in patients’ rooms. We worked very hard under Mrs. Akagawa’s supervision.

However, we were not prepared for such an experience. We worked a 12-hour shift from 7 a.m. to 7 p.m. with an hour for lunchtime. It was hard work.

I had never seen a dead body before I worked in the hospital, but there I saw many bodies every day. The funeral parlour was too busy to remove the bodies immediately, so the bodies were left on the beds. I was initially shocked to see so many of them. As I worked every day, I got used to seeing them.

The room I worked in had about eight middle-aged patients. One of them had a high fever and talked constantly about her children. Another woman tried to leave the room. I had to supervise her. I also talked with other patients who had high fevers.

One day Mr. and Mrs. Taira entered the hospital with their child. They did not appear to be ill. Mrs. Taira was three months pregnant at the time. Most patients in the early stages of pregnancy did not survive. Mrs. Taira and her husband died three days after arriving.

Their child was orphaned. Some staff members looked after the child, in particular a man who had returned from the war. He always carried the child on his back while working. One elderly woman was very kind and said, “Because I have enough money, please look after the child, no matter the cost.” I could not forget her kindness.

A patient gave birth to a baby while staying in the hospital. Mrs. Tateishi helped with the delivery.

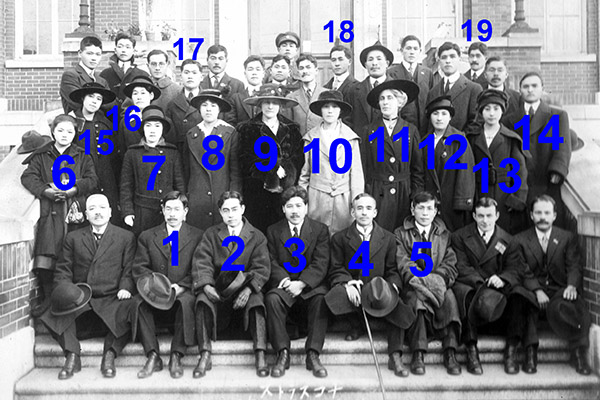

This photo was taken on November 11, 1918, when the temporary Spanish flu hospital at Strathcona School was about to close. The photo shows the volunteer staff of the hospital standing in front of Strathcona School. At this time, Tsune Yatabe was a patient in the hospital. 1: Dr. Yasuo Takahashi, 2: Dr. Akinosuke Ishihara, 3: Reverend Yoshimitsu Akagawa, 4: Consul Satoji Ukita, 5: Dr. Kozo Shimotakahara, 6: Miss Suzuki, 7: Mrs. Tanii, 8: Mrs. Suno Yamazaki, 9: Miss Etta DeWolfe, 10: Mrs. Yasuno Akagawa, 11: Miss Jessie Howie, 12: Mrs. Yoshiko Nakano, 13: Mrs. Sadako Kawabe, 14: Mr. Tsutae Sato, 15: Miss Tadako Hibi, 16: Mrs. Nakamura, 17: Mr. Fujita, 18: Mr. (later Reverend) Kosaburo Shimizu, 19: Mr. Sentaro Uchida. The man in the front row, on the left, may be Mr. Mohei Sato. Photo courtesy: Thomas Fisher Rare Book Library, University of Toronto, Kosaburo Shimizu papers.

I felt very tired for a few days. Normally because I started work early in the morning, I had a good appetite by lunchtime. However, one day I did not feel like eating lunch. I asked Mr. Fujita to take my place, and went home to rest. I completely forgot that we had been told that if we felt ill, we should not go home, but stay in the hospital. I went home because I was concerned about my children. While in bed at home, I began to worry that I was infected.

I telephoned some doctors, but could not reach them. After waiting until the morning, I saw Dr. Shimotakahara and learned I was indeed infected. He admonished me for not following the doctors’ advice. The ambulance came to my house and took me to the hospital. I had a high fever at the time. My oldest child cried when he heard that anyone who was taken to hospital by ambulance died.

My husband also developed the flu and came to the hospital with our 18-month-old son. Fortunately, they were able to leave the hospital after a few days. I learned this later. I was overwhelmed when I saw my father standing at the hospital gate, wearing fine clothing. I spoke to him in my dream.

The flu gradually subsided, but my high fever continued. Four doctors lost hope and gave up on me. I was told I was going to die. Many patients visited me after learning I was not going to live much longer. Doctors wanted to keep me in quarantine in a different hospital because my condition was very serious. However, my fever suddenly disappeared. The doctors thought it was a miracle. They decided to let me remain in the hospital and hoped I would recover soon. I learned this later and I appreciated their work on my behalf. The hospital became quiet after many patients recovered and left. Few doctors and nurses remained working there.

On the last day, Mrs. Hokkyo had a bad cough, and I was asked if she could stay in my room. We were the last two patients. Mrs. Hokkyo kept calling the staff, but nobody came to our room. She began to cry. Three staff members were in the office, but the office was very far from our room. I felt sorry for her, so I got out of bed and crawled all the way to the office. When I returned to the room, I tried to get on my bed, but fell off.

I later learned the reason why no one came to our room. Later that night, it became very noisy outside. News from the battlefield often came to the hospital, and the three staff members were excited to hear the news about the end of the war. Many people were honking their car horns and making celebratory noises. I was allowed to return home on that exciting day. I was in a car decorated with flags from different countries. It was Nov. 11, 1918, a historic day for not only the world but also for me.

As I had been about to die three days before, it felt strange to be alive. At the same time, I felt very sorry for many friends who lost their lives to the Spanish flu.

***

For Tsune Yatabe’s original Japanese essay: http://heritage.canadiana.ca/view/oocihm.lac_reel_c12833/348?r=0&s=2

(Image 348 to 381)

28 Jul 2020

28 Jul 2020

Posted by Susan Yatabe

Posted by Susan Yatabe

4 Comments

This is an important piece of historical analogical document. A hundred years later we are faced with similar fears and mortalities with our current pandemic. Good that Ms.Tsune Yatabe had the foresight to document this part of her experience.

Thanks for forwarding this. So valuable to have this history, not only about this time, but also about the community and specifically about the people. Her memoir also reveals her own personal experience with the flu, her own near death and her wonderful character. It is a real gift.

Susan, I found this online and loved your account of your family history. I remember you fondly from Deep River and how kind you always were. My condolences on your brothers passing. You will carry your families history forward.

[…] influenza outbreaks in 1918 (Spanish flu) and 1934, mask-wearing to prevent cold and flu spread became widespread. By then, mask-wearing was […]