Tamaki’s stories are thoughtful and diverse, but not just for the sake of being diverse. The cover of This One Summer, written by Mariko Tamaki and illustrated by Jillian Tamaki.

OAKLAND, Calif. — Every month, handfuls of new graphic novels are published by comic book powerhouses like Marvel and DC, and even more in the indie comic book scene. Most comics have their own cult followings and fanbases, and there are few that stand out and are universally loved by readers.

One of those voices to emerge on top is Mariko Tamaki. Comicbook.com has raved, “Mariko Tamaki is the best new superhero writer of 2018.” Tamaki, 43, was born and raised in Toronto and currently lives in Oakland, Calif. She is an award-winning young adult author.

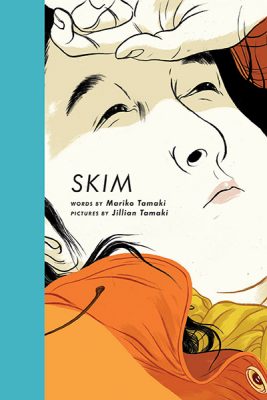

The cover of Skim, written by Mariko Tamaki and illustrated by Jillian Tamaki.

She has collaborated with her cousin, Jillian Tamaki, on the award-winning graphic novel, Skim (2008), about a young, mixed-race Japanese Canadian girl, who feels like an outsider and learns hard life lessons about depression, love, heartache and sexuality. The book received a laundry list of awards and nominations, including winning the Doug Wright Award for best book of 2008 and being short-listed for the Governor General’s Literary Award.

The Tamaki cousins collaborated again for This One Summer (2014), which received the prestigious Caldecott Honor. The story oozes with nostalgia, from its graphic designs that look like classic manga, or even a vintage photograph with its purple hues, to its story of summer adventures that take you back to the sounds and feelings of your own childhood summers.

Along with the awards, the American Library Association announced the book was ‘the most challenged book of 2016,’ in the US. The list is determined by reported complaints made about the book to libraries or schools. It is important to note the top five most challenged books were reported for containing LGBTQ (lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer) themes, characters or content.

Tamaki is recognized for her thoughtful writing style and realistic dialogue. She writes attentive stories with a range of diverse characters, not for the sake of being diverse, but to tell great stories. Her books often are coming-of-age stories, where her young characters learn important lessons about life and tread into big ideas that are revealed through a lead up of small actions. Her stories are never in-your-face, but carefully take you by the hand and lead you on an adventure.

Tamaki took some time to answer some questions for Nikkei Voice about her writing career, the inspiration behind the characters she creates and working with her cousin, Jillian.

Nikkei Voice: How did you start as a writer? What were some of the greatest challenges and highlights?

Mariko Tamaki: I got my start as a writer in high school. I had an amazing creative writing teacher, Rosemary Corbett, who gave me a ton of support and was my first editor. I think she actually taught me how to take an edit as a means of writing better as opposed to a criticism.

I think the greatest challenge to writing is staying with it. For most writers, it is a LONG GAME, and you have to stick through drafts, and not finding places for your work, crippling self-doubt, all of that fabulous stuff. You have to see the big picture, which is the writing itself. Which is difficult when you’re stuck on a second paragraph.

The highlights have been the artists, editors and publishers I’ve worked with. The readers I’ve met. All that.

NV: Why is it important to feature diverse stories in young adult/teen and children’s literature? Why do you focus on characters who are different?

MT: I feel like that question needs to change. In part because it is generally asked of writers and artists that are “diverse,” and I feel like we have spent a lot of time arguing for the importance of diversity. At some point whoever is on the other side of this case needs to explain why diversity ISN’T important. Like, what is the argument there? Why wouldn’t you want a diversity of characters to reflect the great diversity of experiences (of race, class, community, gender, sexuality) that exists out there in the world?

What is the benefit of there being just one story, one protagonist? It sits on the assumption that there is one universal and by now I think we all just know that’s not true. Maybe the argument is against change, because change requires effort, but change is crucial. Change is HAPPENING. I focus on the details of character, which is really the best part of writing. I focus on specifics.

NV: Do you feel your Japanese Canadian identity influences your writing?

MT: Yes, but I am always at odds to explain exactly how that is true. I have always assumed that my dry sense of humour comes from my dad who is Japanese Canadian but that’s an assumption.

NV: What was it like hear This One Summer was the most challenged book of 2015? In some ways does it feel like an affirmation that you are telling a different story to young people?

NV: What was it like hear This One Summer was the most challenged book of 2015? In some ways does it feel like an affirmation that you are telling a different story to young people?

MT: I think it was partly a result of us receiving a Caldecott Honor, which is generally a recognition that goes to a children’s book. I think it’s a list that reminds people of a practice of censoring that takes place in schools and in libraries, and I think it’s worth thinking about how some ideas are more challenging than others, and why. I think we were generally in good company, but I also think that the list means that there are readers, readers who depend on libraries to get access to books, that are being denied books. So that’s not a good thing.

I didn’t see it as a reflection on the work Jillian and I were doing per se.

NV: For many young readers, your books may be the first time they read or learn about topics like depression and sexuality, like in Skim, how do you take on that challenge? What kind of responses have you gotten from your readers?

MT: I feel like more and more I’m aware that these books are connecting young readers to an experience or topic that might be new to them, or a topic that isn’t generally discussed, but I really try not to think about that in the writing process. I try to focus on being as true to the character, story and context as I can be.

We have always gotten incredibly heartfelt responses from readers about Skim and This One Summer and it means a lot. It’s an incredibly rewarding part of writing. To anyone reading this, it is always awesome to share your love of a book. So, hooray.

NV: What do you think is the advantage of creating a graphic novel to reach out to young readers versus a novel?

MT: I don’t necessarily see one or the other as having an advantage. I think there are different groups of readers, some who are more drawn to comics and some who are more drawn to prose, and there’s a lot of overlap and movement between the two.

I think there are different things you can focus on and do with each medium. For me it’s a chance to work with someone else versus working on something solo, which are both things I like to do and come with their own challenges.

NV: How do you create your characters, are they based on people you know or your own experiences as a teenager? Which character are you closest to and which are you most fond of?

MT: It depends. Usually it all comes out of a single detail that I know in the beginning, which develops as I write. Often it’s something inspired by something from my past, but it goes in a very different direction once I start writing.

There are some characters, like Skim, who are much closer to me than others, but they’re all a little me. I know this because my friends tell me this, all the time.

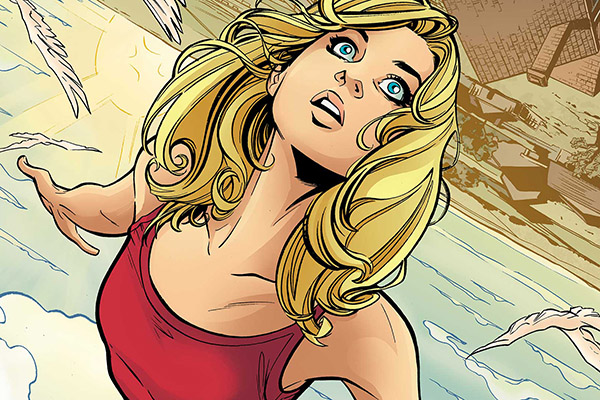

Supergirl: Being Super is Mariko Tamaki’s new project with Joëlle Jones. She is also working on comics about Harley Quinn and Hulk.

NV: Currently you’re working on Supergirl, Harley Quinn, and Hulk comics, among many others, is it exciting to be creating superhero stories in a time where people are so into superheroes, and there are so many fans? Do you find people are currently more willing to accept more diverse superhero stories?

MT: I love working on these different characters, it’s a very unique challenge. Writing into these stories, you’re writing into a very rich history, but also an evolving cast of characters who are evolving as these series are passed on to different writers and artists. I am inspired by the works of people like G. Willow Wilson and Gene Yang, who have created amazing works about characters like Ms. Marvel and Superman.

NV: You have collaborated with your cousin, Jillian on Skim and This One Summer. Did you and Jillian grow up close to each other? Did you base This One Summer characters, Windy and Rose’s relationship on yours growing up?

MT: Jillian grew up in Calgary and I grew up in Toronto, so we were very far apart. I think we both brought our own separate histories of being a kid to this book.

NV: When researching This One Summer, you actually went up to Muskoka together. What was that like, are there any anecdotes from your trip that ended up in the story?

MT: We did. I don’t think there were any anecdotes from that trip that made it into the book, I do think that a lot of detail from that trip, from the things we saw and Jillian photographed did.

NV: Is it helpful to have a cousin who also works in a creative/literary field, have you turned to each other for advice or support while creating stories?

MT: It is an amazing thing to be related to someone as insightful and talented as Jillian Tamaki.

***

12 Sep 2018

12 Sep 2018

Posted by Kelly Fleck

Posted by Kelly Fleck