From May 26 to 28, the new dance theatre performance, Enemy Lines, played at McMaster University’s Black Box Theatre in Hamilton, Ont. The remarkable dance theatre choreographer and principal contemporary dancer, Toronto-born and raised Yonsei Mayumi Lashbrook, was accompanied by a supporting dance ensemble of four diverse, talented young contemporary dancers, Brayden Cairns, Miyeko Ferguson, Michael Mortley, and Denise Solleza. The performance was produced by the Hamilton-based Canadian contemporary dance company Aeris Körper, with which Lashbrook is a co-artistic director and part of since 2014. She has performed in numerous Hamilton-based past productions—such as Hamilton’s popular annual Art Crawl and the Hamilton Fringe Festival.Mayumi Lashbrook in Enemy Lines, which ran at McMaster’s Black Box Theatre in Hamilton on May 26 to 28. Above is Lashbrook during the Toronto performance at Theatre Centre, May 12 to 14. Photo credit: Marlowe Porter.

In an April 2023 interview with Nikkei Voice, Lashbrook describes the initial inspiration (the anti-Asian backlash during the pandemic) and the two-year process behind crafting the performance, from interviewing her maternal family members to researching her great grandparents’ internment case files in the Landscapes of Injustice database. Lashbrook gives a large nod to her mentor and dramaturg, award-winning Sansei dance artist and cultural force extraordinaire of 45 years, Denise Fujiwara. Among a long resume of impressive accomplishments, Fujiwara is a CanAsian Dance co-founder.

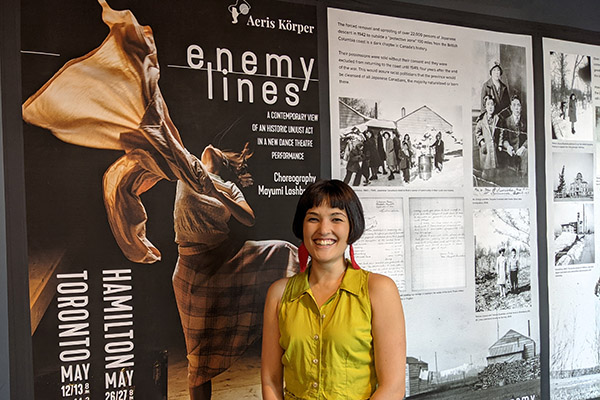

Dance artist Mayumi Lashbrook in front of the poster displays with her family’s history. Photo credit: Karen Uchida.

A triptych of large museum-quality graphic design posters established the theme and narrative of Enemy Lines. Included were old historic black-and-white family photographs that depict the painful journey of Lashbrook’s maternal ancestors from their home in Strawberry Hill, B.C. to the sugar beet farms of Manitoba, to war-torn Japan in 1946. An iconic photo of Hiroshima after the atomic bomb was dropped and a historic personal letter written to the government from Lashbrook’s great-grandmother retrieved from the Landscapes of Injustice database. The last two posters read:

“The forced removal and uprooting of over 22,000 persons of Japanese descent in 1942 to outside a ‘protective zone,’ 100 miles from the B.C. coast is a dark chapter in Canada’s history. Their possessions were sold without their consent, and they were excluded from returning to the coast until 1949, four years after the end of the war. This would assure racist politicians that the province would be cleansed of all Japanese Canadians, the majority naturalized or born there.

Using dance as the medium, Mayumi Lashbrook weaves the story of her great-grandmother’s experience through this ordeal and helps herself work through the inter-generational trauma left in its wake. How can the lessons from these past wrongs bring awareness and understanding of the ongoing oppression of so many minority communities throughout the world that still occurs today?” The printed program, handed out before entering the theatre, incorporates the same historic images.

Mayumi Lashbrook in Enemy Lines, accompanied by a supporting dance ensemble of four diverse, talented young contemporary dancers, Brayden Cairns, Miyeko Ferguson, Michael Mortley, and Denise Solleza. Photo credit: Marlowe Porter.

Enemy Lines is a fluid and engrossing narrative performance that through the artful blending of theatre, performance art, and contemporary dance, reveals a family’s painful history and a shameful period in Canadian history. With a handful of key props, including a symbolic trunk, bed sheets/cloth, minimal costumes, luggage pieces, dramatic lighting, transitioning period music, dramatic audio, and a handful of projected historic images and period films. Lashbrook’s facial expressions and body was extensively used to convey the emotional states and traumatizing experiences her great-grandmother endured, as well as the inter-generational trauma she experienced herself. All the choreographed dramatic movements of the dancers flowed cohesively with athletic physical beauty in every scene to support the narrative and theme. Colour was muted in all the costumes and appeared almost monochromatic so that the symbolic movements of the dancers took visual precedence. The ubiquitous use of cloth to emphasize and extend the dancer’s expressions and symbolize space and objects, as well as serve as a screen for a few projected images, was creatively used throughout the performance.

The one-hour performance opened with Lashbrook appearing on an empty dark stage in contemporary clothes, reflecting the present day. In the middle of the stage sits a trunk under a white cloth. Addressing the audience in her own voice, she first delivers a land acknowledgment to the original Indigenous tribes of the past 15,000 years to the theatre’s site and gives a poetic introduction. “My great-grandmother was a chest of memories refusing to be opened. When I began to ask why, the answer sprung out from the amniotic deep of my maternal line…the answer points back to a sliver of time some hope to forget, when the face of the enemy looked like mine, when a worn-out bed sheet became a home, when lives were forced to fit inside a trunk.”

Lashbrook removes the sheet from the chest in the middle of the stage, hangs it on a line, opens the trunk, and removes some clothes. A historic photograph of her great-grandmother and three children is projected onto the hung cloth. Lashbrook introduces her maternal ancestors to the audience, “this was the time of my great grandmother, Tsuyako Sumioka, a young bride, a grateful immigrant, a mother of three Canadian-born children and then suddenly a widow, she had to be hard-working…her eldest was Nobue, 14…then Tatsui, 11…then little Yukia, just five years old…I can’t help but wonder what it would have been like to grow up in this time…” and begins to change behind the hanging cloth. She emerges dressed in a vintage A-line plaid skirt and short sleeve sweater. Lashbrook is now transformed into her young great-grandmother, Tsuyako Sumioka. She dances joyfully with a swirling cloth retrieved from the trunk. Audio of vintage Japanese western-style music plays from a scratchy, old record, and she incorporates a riff on the Bon Odori dance Tanko Bushi as life in prewar B.C. is portrayed.

The attack on Pearl Harbor by Japan is portrayed by red lights and dramatic air raid sirens filling the theatre, as the ensemble of dancers emulate dive-bombing Japanese planes, using the cloths as wings. Lashbrook curls up into a ball on the stage, twisting and compressing the cloth expressing the fear and anguish caused by the traumatic event. To mournful piano and string music, Lashbrook then retrieves items from the trunk, leaves the stage, and enters the audience space to hand them to members, and asks in the broken English accent of an Issei woman, “Please hold for me, I will come back,” symbolizing her great-grandmother’s “goal to return and reclaim her belongings.” Unknowingly, it was the beginning of the dispossession of Japanese Canadians. She slowly walks back to the open trunk, now representing her home, climbs into it, turns sadly, and hides under the cloth. The ensemble dancers, dressed in uniform, march up slowly to her, and she is dramatically dumped out of the trunk, out of her home. The dancers, the RCMP, march away with the trunk, throwing some possessions into it.

Mayumi Lashbrook in Enemy Lines. Photo credit: Marlowe Porter.

To melancholy music, the ensemble dancers lay out two cloths on the stage, representing the wooden shacks on the sugar beet farm in Manitoba her great-grandmother and family were displaced to, and lift Lashbrook’s stiff vertical body onto a cloth. A voice is heard (recorded voice of creative Shin-Ijusha Yukari Peerless) narrating four letters. In increasingly desperate and heart-wrenching letters from 1942 to 43, her great-grandmother wrote to the government—that Lashbrook uncovered in the Landscapes of Injustice database—are projected on the cloth screen. They are futile repeated attempts, asking for the rent arrears from her B.C. farm property (unbeknownst to her has been liquidated), which she never receives and needs to feed her hungry children.

The last letter contains the most painful and haunting words, “Dear Sir, We did not get enough in sugar beet this year and we haven’t enough to eat. So if you’re kind, can you send me $100, something. Sincerely, Tsuyako Sumioka.” Lashbrook retrieves an audience member to join her on the stage, and they mirror her movements to fold and tie the cloths in the traditional method of Japanese wrapping cloths called furoshiki, symbolizing the packing of possessions. Lashbrook utters a few Japanese phrases with the instructions. Then dons the heavy-looking bags on each shoulder and staggers slowly around the stage as the projected dates of 1942 to 1945 scroll down on the screen as sad piano music plays. She finally collapses on stage.

Audio of a male voice (voiced by actor Eric Wigston) is heard announcing in the oratory style of the period that narrated war propaganda in newsreels and on radio, “Notice to all persons of Japanese racial origin: the Ministry of Labour has been authorized…to make the following decisions…make voluntary application to go to Japan. The Canadian government will guarantee to all repatriates and their descendants free passage and transportation…” announcing the government intimidation plan to “repatriate” (a euphemism for exile and expel) Japanese Canadians to Japan. While the 1939 hit single, If I didn’t care, by The Ink Spots plays, the ensemble dancers, still dressed in military costumes, re-enter the stage and pile four pieces of large luggage onto Lashbrook’s arms and carry away the trunk. In formation to a slow, rocking rhythmic march to the beat of the song, they leave. Lashbrook dons a coat, hat, and gloves and picks up the luggage to prepare for her unseen ship’s departure to Japan. A key visual red Maple Leaf develops on the screen and transforms into a red circle resembling the flag of Japan. Lashbrook bows toward the audience and walks off at the period song ending.

Mayumi Lashbrook in Enemy Lines. Photo credit: Marlowe Porter.

A short colour video begins, portraying Japanese Canadians in the internment camps of B.C to upbeat music as Lashbrook re-enters the stage, still dressed in her travel outfit, and a recorded audio voice (voiced again by Wigston) is heard announcing, “Canada’s 22,000 people of Japanese racial origin have been an ongoing menace to our society. There are among them Japanese nationals, naturalized Canadians, and Canadian-born. There are those we have given free passage back to Japan. And those that are striving hopelessly for assimilation. The problem that they pose has been solved only temporarily. They cannot be assimilated as Canadian, for no matter how long the Japanese remain in Canada, they will always be Japanese. The ultimate solution will depend on the measure of careful understanding by us Canadians.” While the ensemble dancers join Lashbrook and assist her in changing back into her contemporary clothes, representing her transition forward in time to the modern day.

Lashbrook solemnly addresses the audience, “Tsuyako Sumioka opted for voluntary repatriation in 1946. She cashed in her life insurance policy to pay for a new start in Japan. They were met with scorn and discrimination, they longed to return to Canada. In 1949, Japanese Canadians were finally allowed to return to the coastal regions that they had been forcibly removed from, but there wasn’t anything to return to, their land had been sold without their permission to low market value. Between 1950 to 1961, my family gradually made their way back to Canada, rebuilding their lives which brings me here, piecing together what happened, looking at the sealed vault of my great-grandmother, at the broken pieces of my shattered family, and trying to understand.” Behind her, the dancers return and erect two cloths as screens.

Lashbrook seats herself facing the cloth screen, and a video clip plays of an old black-and-white government history (propaganda) film with a male voice narrating, “War it came again to Europe in 1939, it moved on to a new climax at Pearl Harbor in 1941, within a few hours…Canada was at war with Japan. Fear of attack became suddenly real. With war in the Pacific, it came to nationwide attention that Canada had 23,000 residents of Japanese racial descent who practically all lived and worked inside the Western no 1. Defence Zone. In 1942, it was decided all people of Japanese racial origin should be removed to the interior of B.C. and other parts of the dominion.”

The short video depicts images of Japanese Canadian residential and commercial buildings in coastal B.C. before 1942. To sombre, gradual music, Lashbrook reacts to the film, dancing expressively and dramatically, emoting anger with expansive movements. The four dancers appear to remove the two cloth screens and restrain Lashbrook by wrapping and tying her with tension as they hold her trapped in the middle between four held ends. Eventually, Lashbrook collapses on the floor, then grasping her knees, speaks dramatically, “22,000. 22,000 people of Japanese racial ancestry displaced by RCMP in 1941, of them 5,562, only a quarter, were Japanese Naturals, 3,223 naturalized Canadian citizens, 13,309 were Canadian-born. Zero. Zero acts of spying. Zero acts of treason. Zero acts of sedition. Not one.”

Mayumi Lashbrook in Enemy Lines, accompanied by a supporting dance ensemble of four diverse, talented young contemporary dancers, Brayden Cairns, Miyeko Ferguson, Michael Mortley, and Denise Solleza. Photo credit: Marlowe Porter.

Subsequently, the entire dance ensemble returns to the centre of the stage, and each dancer takes turns in circles, raising fists and announcing in escalating speech and physical aggression toward the previous speaker. A list of ongoing unjust oppression’s of minorities and peoples occurring currently in the world, beginning with “Ukraine, the illegal annexation of Crimea by Russia; Canada, disproportionate incarceration of Indigenous groups, China; Uyghur re-education camps; Japan, displacement of unacknowledged Ainu People; India, persecution of non-Hindu groups; Syria, arrested and missing civilians and more, ending with a loud, deep shout Canada!

Next, under a red spotlight, to harsh, drumming-heavy music, the dancers first move in synchronized slow motion, their movements and expressions displaying negative emotions of fear, such as anger, oppression, and shock, then with increasing movements and interactions on the stage, emote isolation, distrust, hate, aggression, and persecution. The music ends abruptly, and the stage darkens to signal the end of the performance.

A number of the Japanese Canadian Hamilton-based community attended the performance over the weekend at McMaster. Descendants of the original internment survivors, who went ‘East of the Rockies’ circa 1947, a few thousand at least, first settled in Hamilton as the city of Toronto refused them. They were clearly moved emotionally and equally impressed as myself by the powerful performance.

Impressed upon learning the producing dance company Aeris Körper was based in Hamilton, it was revealed that Michael Abe, a Sansei born in Hamilton, raised in nearby Burlington, and McMaster graduate, was the historical consultant for Enemy Lines. Abe, living in Victoria since 1993, played a pivotal role as project manager of the seven-year Landscapes of Injustice project. Through email, Abe wrote, “It’s been tremendous to see how the availability of the Custodian of Enemy Property case files has helped many community members explore their family history and has helped the younger generation connect with their ancestors. And it’s even more exciting to see them express their stories in such artistic and creative ways as Mayumi has done, with such power and emotion.” He added, “In helping with some of the historical facts, I consulted Ken Adachi’s book The Enemy That Never Was, the quintessential source for our history despite him not having access to the case files at the time.

As a Sansei, viewing this immersive, incredibly moving performance in the dark, intimate theatre was a sad emotional experience, and many tears were shed. I believe my empathetic reaction would be collectively experienced by any descendant of the Japanese Canadians whose families were affected in this dark chapter of Canadian history. I wonder about collective and inter-generational trauma. Yet my sadness was mitigated by the awe of the creative tour-de-force that the young, artistic genius Mayumi Lashbrook is and the amazing, complex artistic production she created. It saddened me that it was such a small intimate theatre, and this was the last performance of a three-day run for a short two-city tour.

Enemy Lines must be seen by all Canadians and deserves much wider recognition and national distribution. Canadians need to see this important educating performance as this history must not be forgotten, and Canadians must ensure this racist perpetuated injustice of civil rights abuse is never repeated in our democracy. And we must all try our bit to stop these reoccurring cycles of fear and ignorance-based oppressions all over the world and in Canada.

***

04 Aug 2023

04 Aug 2023

Posted by Karen Uchida

Posted by Karen Uchida