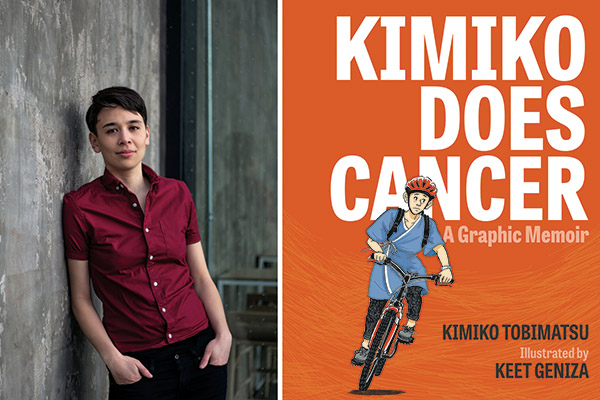

Author Kimiko Tobimatsu shares her experiences as a queer, mixed-race woman with cancer.

TORONTO — At age 25, Kimiko Tobimatsu‘s life was upended when she was diagnosed with breast cancer. Her life became a balancing act of medical appointments and her full time job articling at a law firm. Her social life, relationship, and plans were put on the back burner while she tried to navigate a cacophony of medical advice.

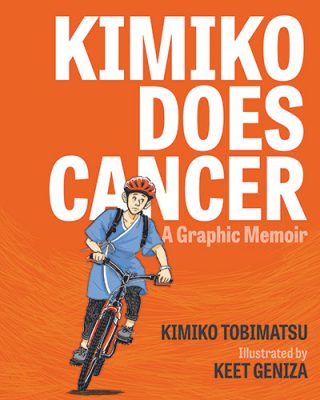

During her treatment, Tobimatsu found she craved connection with people going through similar experiences as her. As a young, queer, mixed-race woman, the search for patients and survivors with similar viewpoints and experiences was hard-pressed. Tobimatsu set out to create the book she would have liked to see during her cancer treatment. She gets personal with her honest, candid voice, shares her experiences, and challenges the dominant cancer narrative in her new graphic novel, Kimiko Does Cancer.

Kimiko Tobimatsu is human rights and employment lawyer and the author of Kimiko Does Cancer. Photo credit: Jenny Vasquez.

“It’s definitely not something I imagined doing at all or thought of before cancer happened,” Tobimatsu tells Nikkei Voice in an interview. “I got cancer and then was in these bizarre experiences and situations, and started doodling about it. At the same time, [I was] reading up and trying to find folks that I could relate to and wasn’t finding a lot out there.”

Through Tobimatsu’s personal experiences shared in her book, she thoughtfully critiques the prevalent dominant narrative of what a breast cancer patient should be. The standard image we often see is a white, straight, feminine woman, explains Tobimatsu. Breast cancer and its treatments affect a woman’s breasts, hair, and fertility, notions deeply associated with femininity. Consequently, resources for breast cancer patients often focus on support for the loss of femininity, and how that affects straight marriages, or breast reconstruction after a mastectomy, all tied up with a pink bow.

While all valid and important concerns, if you do not identify with those ideas of gender, it can be isolating. It can feel like you are being told what you should do, feel, or want, versus being asked what you need, says Tobimatsu.

One in eight women in Canada will be diagnosed with breast cancer in their lifetime, and an estimated 27,400 will be diagnosed with breast cancer in 2020, according to the Canadian Cancer Society. This dominant narrative cannot possibly represent all of these women. By focusing on only one demographic, others’ lived experiences are excluded, which can perpetuate the inequalities in our healthcare system, and also leads to gaps in medical care. A study from the University of Toronto last year found Canada severely lacks research on Black women and breast and cervical cancer. The study examined 2,000 studies on cancer published between 2003 and 2018, where only 23 focused on cancers in Black patients.

The cover of Kimiko Does Cancer, by Kimiko Tobimatsu and illustrated by Keet Geniza. Photo credit: Arsenal Pulp Press/Kimiko Does Cancer.

Breast cancer messaging, especially during Pinktober or Breast Cancer Awareness Month, often narrate cancer treatment as a fight or a battle. This image can be quite isolating for people who have metastatic breast cancer, never went into remission, or are continuing to fight, says Tobimatsu.

“I’m on ongoing medication, and so while I don’t have cancer anymore, I’m still dealing with the effects of cancer and the treatment and so I don’t necessarily feel triumphant,” says Tobimatsu. “I think that has an implicit suggestion that if you didn’t win if you are going to die from cancer, that you didn’t fight hard enough, and of course that isn’t true, it’s completely out of our hands. But I think it holds people up to that expectation, you have to give it your all and fight and be peppy throughout because that’s the image we want to see of who breast cancer patient is.”

Tobimatsu was diagnosed with oestrogen breast cancer, which is a hormone-sensitive cancer. While she no longer has cancer, her doctors don’t have a definite cause of her cancer. To minimize the risk of the cancer returning, she takes ongoing medication that induces early menopause and causes uncomfortable side effects, like hot flashes. With honesty and vulnerability, Tobimatsu’s memoir shares how cancer has changed her life. She shares experiences dating in her 20s while in menopause, learning how to ask for help, difficult conversations with her family and friends, and navigating well-meaning but unhelpful advice.

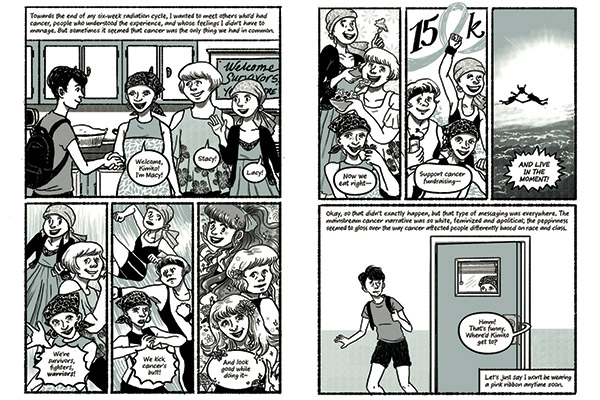

An excerpt from Kimiko Does Cancer, by Kimiko Tobimatsu and illustrated by Keet Geniza. Photo credit: Arsenal Pulp Press/Kimiko Does Cancer.

Tobimatsu’s story is beautifully brought to life with illustrations by artist Keet Geniza. When Geniza started working with Tobimatsu in March of 2017, the project went from a 20-page zine to a 100-page graphic novel. Geniza is also a queer, Asian woman whose life was affected by cancer after her father was diagnosed with stage IV cancer. Geniza pushed Tobimatsu to go deep and get personal with her story, helping it evolve to what it is today.

“Keet helped me understand that art is vulnerability,” says Tobimatsu. “[I wanted] to make something helpful to other people. I know as a reader myself, when I’m reading something that is vulnerable and is sharing intimate details, I’m more likely to relate and see myself in that, so I wanted to be able to do that as well,” says Tobimatsu.

With few stories in mainstream media like her own, Tobimatsu blazed her trail, navigating cancer treatment and life after cancer. Behind her, she leaves a path paved for anyone who doesn’t feel the mainstream cancer narrative fits, to find comfort and company during a time where she felt so isolated and alone.

***

For more information or to purchase Kimiko Does Cancer, visit: www.kimikodoescancer.com.

They’re here and beautiful and we’re just so overwhelmed! Get your preorders here: https://t.co/WrRXC2FsCd pic.twitter.com/LO0b4bXLnf

— Kimiko Does Cancer (@kimikotobimatsu) August 12, 2020

17 Nov 2020

17 Nov 2020

Posted by Kelly Fleck

Posted by Kelly Fleck