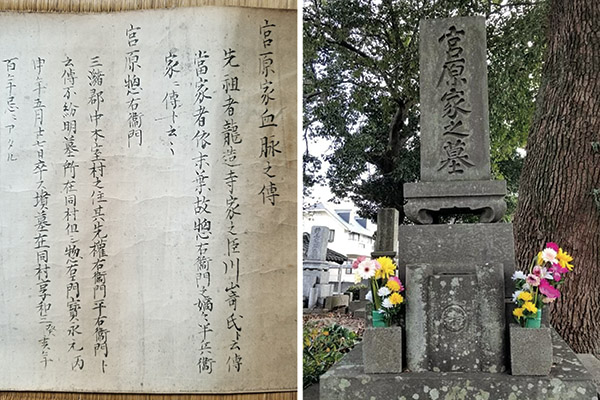

Left: A photo of the Miyahara family genealogy scroll, handwritten by Fumiko’s great-great-grandfather, Rikichi Miyahara. Right: The Miyahara family grave. Photos courtesy: Fumiko Miyahara.

In the first part of this article, Fumiko Miyahara writes about discovering her family’s genealogy scroll. Around 2.5 m long, the family scroll was beautifully handwritten by Fumiko’s great-great-grandfather, Rikichi Miyahara. The scroll covers over 200 years of family history, starting with Miyahara’s ancestor, So-uemon Miyahara, who died in 1704.

Read part one in the October 2022 issue of Nikkei Voice, where Fumiko translates and uncovers her family’s history as retainers of the House of Ryuzoji, one of the three mighty warlords of Kyushu, to living through the end of the Edo Period and beginning of the Meiji era.

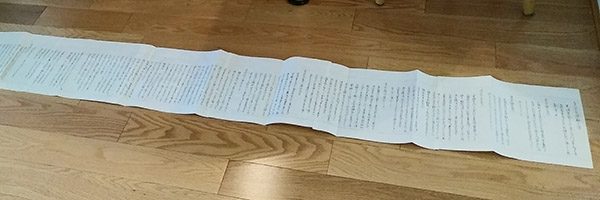

The Miyahara family scroll was over 2.5 m long and covers over 200 years of family history. Photo courtesy: Fumiko Miyahara.

Part II

The scroll ended with my great-grandfather Yoshitaro Miyahara’s (1860-1925) entry. It was apparent that he wrote in additional information on his father Rikichi, such as the date of Rikichi’s death, as well as the information on his own wife and children. The handwriting was completely different.

Because I was the only one in my generation who was retired with “lots of” time on hand, once the scroll translations were done, my next project was to continue the genealogy, adding the information on my grandfather Miyahara and my father’s generations.

It became clear that we did not know enough about our grandfather. I felt I needed to add at least the same level of information as there was on the scroll for other ancestors. There was a rumour that our grandfather had a first wife, but they divorced because she could not bear any children. None of us knew her name or how long they were married. We did not know our grandmother Miyahara’s maiden name or her father’s name.

What becomes useful in these cases is a document called koseki tohon. (Tohon is a copy of the entire koseki, while shohon pertains only to the individual). I’m sure that many Nikkei people are familiar with koseki. The koseki system registers all Japanese citizens by household under a household head and records milestone information on the individual, such as the date of birth, relationship to the household head, parents of the individual, date of marriage, date of adoption, date and reason for removal from that particular koseki, or date of death. All are in one place.

Another unique feature of koseki is that it is associated with honseki (registered domicile or the city/town/ward the Japanese citizen considers to have their roots), which is often the address where the household head was born. It can be a puzzle to figure out where an individual’s honseki is. But it holds key information one needs to know because koseki is maintained by municipalities. A koseki copy must be requested from the city hall where the honseki/permanent domain is.

I decided we needed our grandfather’s koseki tohon to learn more about him. The national koseki system in Japan came into place in 1871. My grandfather was born in 1886. (The year is based on koseki. The engraving on the Miyahara tomb differs by a couple of years.) Only one, their spouse, or direct descendants, such as a child or a grandchild, can request a copy of koseki, so I asked my brother in Japan to obtain it.

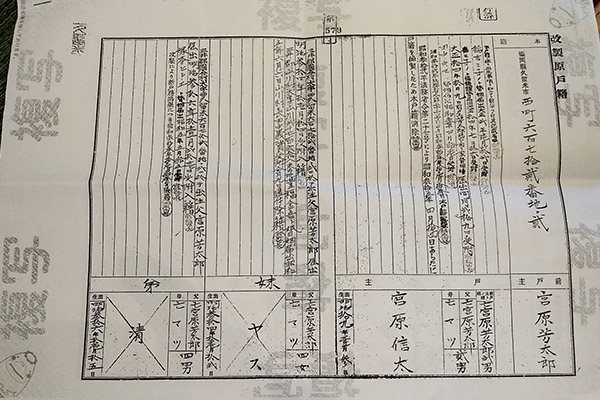

Fumiko’s grandfather’s “Original Koseki prior to Amendment” page 1. There are 5 pages in total. Any removal from his koseki after the amendment is captured in a separate document called “Removal of Seki.” Note: “Ko” in “ko-seki” means household. So, koseki is the registry of a household. Individual registry is a seki. Photo courtesy: Fumiko Miyahara.

It turned out that the koseki tohon of my grandfather, Nobuta Miyahara (1886 – 1969), was a little treasure itself. We learned his first wife’s name. They were married for 12 years! The divorce was filed a couple of months before Nobuta’s father died. Probably, knowing his death was imminent, my great-grandfather thought he had to do something about this heirless situation. We found our grandmother’s maiden name, parents’ names, and address. She was the eldest daughter.

Interestingly, my grandfather’s koseki tohon was entitled “Original Koseki prior to the Amendment.” The law of koseki changed several times in Japan. Probably the biggest change was that the koseki unit changed from the extended family to the nuclear family. (The law came into place in Showa 32 or 1957, but it took a while to implement).

Because my grandfather’s koseki was prepared before that change, it begins with the previous household head’s name. Then, because my grandfather was the official heir taking over the household, his uncle (my great-grandfather’s younger brother) and his family, my grandfather’s younger siblings, came under him. His sisters were removed from his koseki and moved to their husbands’ once they married.

But his younger brother remained under my grandfather even after he married and had children. He and his family were removed only when the amendment took place. So, there were 16 people on his koseki, although many were removed for one reason or another. In the koseki system, officials only cross off the person’s name to remove it from the koseki, so one can still see all the original information. I found out about many distant relatives whom I did not know.

There is a koseki for anybody who was once a Japanese citizen. Even if your parents, grandparents, or great-grandparents became Canadian citizens many years ago, giving up their Japanese citizenship, their koseki records are kept in the applicable city halls.

Fumiko Miyahara’s cousin at the Miyahara family grave. He worked to clean the graves and graveyard in preparation for Obon. He is the last Miyahara to look after the gravesite. As he does not have any children, the family does not know what is going to happen in the future. He does not wish to adopt a child to pass on the responsibility of looking after the graves. Such adoption is also becoming extremely difficult because there are not enough children. “Who is going to look after the family grave?” is becoming a common problem in Japan nowadays. Photo courtesy: Fumiko Miyahara.

Another thing I found out is that neither my grandfather in his second marriage nor my father legalized their marriages until they knew for sure that their wives could produce offspring. I learned the ‘anniversary date’ my parents had told us was their wedding day, but they were not legally married until seven months after the wedding and five months before I was born (I am the eldest). What pressure it had been for my mother that their first two children were girls.

It is not easy to get a copy of koseki from outside Japan. Now, municipality websites say people can request the documents by mail. In addition to proof that you are the person you claim to be plus proof of relationship if you are not requesting a copy of your koseki, it has to be accompanied by a money order issued by the Japanese postal office for fees and a return envelope with the Japanese postage. And all the forms are in Japanese only. What can one expect? Koseki is the registry of Japanese citizens. Therefore, people pretty much need help from somebody in Japan to obtain a copy of koseki. Then, you must hope that you or this person knows the honseki/permanent domain of the individual.

My brother moved his honseki when he bought a house for the family. Until then, his honseki was the birthplace of our father, in Kurume, where my brother lived only for the first 10 years of his life. My mother’s honseki is the same place in Kurume, where she lived for about 13 years, while she has lived in the house my father built in Chiba for over 40 years. Her home in Chiba is her permanent address in every way, but my father did not change his honseki before he died, so my mother is not going to either.

A little message for post-Second World War first-generation immigrants from Japan like me: Many of us married non-Japanese-speaking Canadians. If available, get the koseki tohon of your father, grandfather, and great-grandfather, in addition to yours, while you still have people who can help you in Japan.

Translate them and leave them for your children. I think it will be much appreciated in the future.

***

22 Nov 2022

22 Nov 2022

Posted by Fumiko Miyahara

Posted by Fumiko Miyahara