Eva Hashiguchi isn’t at all shy when it comes to talking about her internment experience.

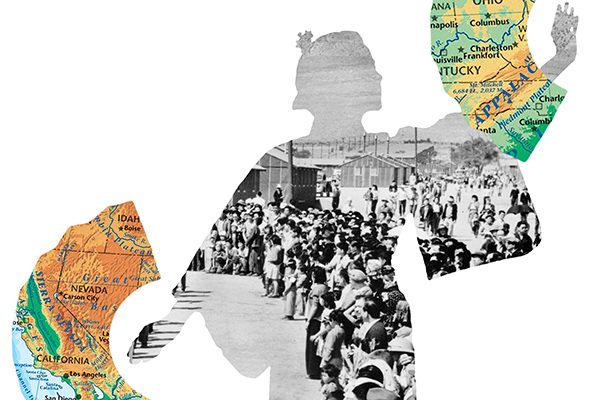

Born on the West Coast, Hashiguchi, her six siblings, and parents were sent to Jerome, Arizona and then to Rohwer, Arkansas soon after the United States entered into World War II.

It was a long time before their family founds their roots again, but eventually they settled in the North Eastern United States.

It’s a story many Japanese Americans and Japanese Canadians tell, but Matthew Hashiguchi, her grandson, is working on a new project called Good Luck Soup that aims to tell the story of what happened before, during, and after.

“I think that this is an experience and an identity that’s slowly starting to fade away,” Matthew Hashiguchi tells Nikkei Voice.

“I want to make sure it’s preserved, but not just their experiences during, but also after,” he says. “What did they do to re-establish their lives? They are really the reason why we are here and who we are.”

And it’s the stories he’s heard all his life that help inspire this project.

Mitch, right, and Bev, left, Hashiguchi. Photo courtesy: Matthew Hashiguchi

Eva Hashiguchi’s family moved from internment camps to Louisiana in the far southern U.S to restart their family farm.

In a racially charged environment, she saw segregation and experienced the worst forms of racism imaginable.

When word came that Jewish businesses in Cleveland were taking in Japanese Americans, their family picked up their things and moved.

It was there they found a burgeoning community that had close ties to places like Toronto where other Japanese had resettled.

Years later, Matthew Hashiguchi was born.

Growing up in a mostly Irish neighbourhood in Cleveland, Ohio, Hashiguchi faced his fair share of discrimination being Japanese American.

“Jap,” “Gook” and “Chink” were slurs that were part of the every day fabric for him and his brother and sister. Although he would fire back with slurs of his own, the struggle didn’t seem to end with his parents and grandparents.

It’s this reality, along with the many triumphs against adversity the community has seen, which Hashiguchi wants to allow users online to write about online.

“Many of the stories I’ve received have shown me the character of these people and some of it’s sad, but most of it is positive,” Hashiguchi says.

“I think most of the feedback I’ve received have been from Sanseis, people who are 40 or 50 years old,” he says. “They’ve been interested in sharing their stories about their family members.”

Hashiguchi is in the unique position of having a grandmother who is exceptionally open to talking about her experiences. She’s even able to crack jokes about struggles, but there’s always pain.

During the initial stages of his project, Hashiguchi reached out to Cleveland’s Japanese American community to raise awareness. Although many Sanseis were interested in the project, a few were reluctant to bring up this largely undisturbed past.

Every Japanese American has a file from internment.

Some of them are hundreds and hundreds of pages long and contain personal information, according to Hashiguchi.

With the right forms, American citizens can get access to their files, but Hashiguchi found some didn’t even want to think about opening theirs.

“A couple of Sansei people were rude and dismissive in saying, ‘We don’t need to talk about this. Why are we talking about this? We should move on. Who cares’,” Hashiguchi says.

“It’s important history and I think people that are our age who are third or fourth generation it’s important to use,” he says.

“It’s something we want to discover or uncover because many of our grandparents really don’t want to talk about it.”

***

Although there has been a little apprehension from older members of the community, younger Japanese Americans are excited to share their family stories.

Users can go online and enter in their family story through the project’s interactive website.

Entering in where their families were interned or where they families went to after the Second World War, users can upload text and photos to help illustrate their experiences.

From short snippets to touching memories, they tell stories of who their parents and grandparents were and who they became over the course of time.

But this project also addresses a question of identity that many younger mixed-race Japanese have, according to Hashiguchi.

While many young Sansei and Yonsei may live in places like Cleveland, Ohio or Toronto, Ontario, how did they get there? Why can’t they speak Japanese? Why do they feel so integrated into society and yet their skin colour is different from everyone else’s?

“I think Japanese Canadians and Japanese Americans have made a strong effort to show they belong,” Hashiguchi says.

“It’s like you have to be American, you have to be a good citizen, you have to do this and that because you have to show people you aren’t bad,” he says.

“I think it’s important to look at it from a positive light, not always negative. I wouldn’t have been born if this didn’t happen.”

Hashiguchi plans to go on a road trip with his project to help promote it throughout the U.S. He hinted at possibly taking it to Canada in the future.

For more information, visit: www.goodlucksoup.com

12 Nov 2014

12 Nov 2014

Posted by Matthew O'Mara

Posted by Matthew O'Mara