TORONTO — Mark Sakamoto’s family memoir, Forgiveness: A Gift from My Grandparents won this year’s Canada Reads competition, CBC’s annual “battle of the books.” Photo credit: Peter Power.

Under the theme, “one book to open your eyes,” five Canadian personalities debated the merits of the 2018 selections, that ranged from science fiction to memoir to young adult fiction. The debates were broadcasted over a series of four episodes from March 26 to 29, where the panelists voted one title out of the competition each day until only one book remained.

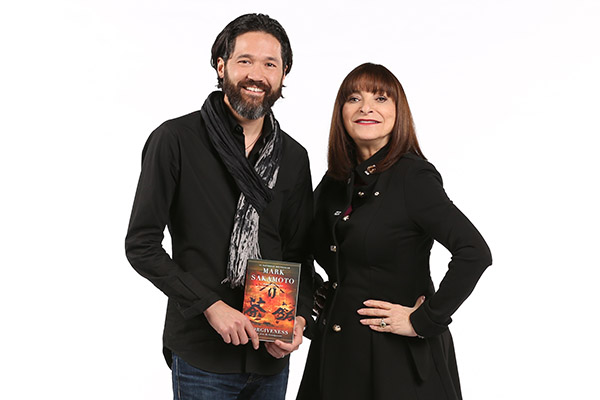

Fashion journalist Jeanne Beker defended Sakamoto’s book. On CBC Radio’s Q she explained why she chose his book.

“Those of us lucky enough to have heard our families’ survival stories firsthand share a window onto a world of unspeakable loss and profound pain. But it’s these very tales of toughness and tenacity that light our paths and often define who we are. Forgiveness sheds light on a shameful chapter in our history, but it also shows us that healing is possible with tolerance and compassion,” she explained. “The message for Canadians is a timely one. Forgive in order to move forward and never, ever forget.”

I am so honoured that Forgiveness was selected as the book to open your eyes this year. Thank you to @CBC Canada Reads for all you do for Canadian literature. And, of course, thank you to the indelible @Jeanne_Beker for holding my family's journey so closely to your heart. pic.twitter.com/hUHTJOX4i5

— Mark Sakamoto (@MarkSakamoto1) March 30, 2018

Forgiveness follows Sakamoto’s maternal grandfather, Ralph MacLean, through his capture and imprisonment as a prisoner of war in Japan during the Second World War, while his paternal grandmother, Mitsue Sakamoto, and her family were interned by the Canadian government.

In an interview with Nikkei Voice in his Toronto office a week before the winner was announced, Sakamoto said, “In some ways it sounds like a dark story, and in many ways it is, but it’s a hopeful story, because I exist and my brother exists.”

“My grandfather wanted to go serve his country and go fight in Europe. He joined the military and the Canadian government sent him to Hong Kong. Three weeks after getting there, he came up against 50,000 Japanese soldiers. His experience was horrific. He was starved and beaten, and he was sent to Japan. On the other side of the world, my Grandma and Grandpa Sakamoto were living rich productive lives as Canadian citizens. At that time [after the bombing of Pearl Harbor], the Canadian government bowed to political pressure and interned all Japanese Canadians. My grandparents were taken from their home, lost their property and lived life in a chicken coop in Alberta,” he said. “Both my grandparents were pushed down by large geo-political forces, but everybody falls down in life; there’s nothing special in that, but what was inspiring was the fact that they got up, and their surviving wasn’t their greatest achievement, it’s how they went on to live their lives. They were extremely heroic, in their own ways, turning darkness into light; it’s the hero who gets up. They were both heroes in my life: The ways in which they were both able to proceed on with life is a universal story that I wanted to share.”

In addition to describing how his parents met, and how both families forgave the past and moved forward, Sakamoto shares his mother’s story. Her descent into alcoholism, from which she eventually died and how, through his grandparents’ examples, he was able to work through his complicated relationship with her and move on. When Sakamoto began writing the book, he says didn’t have the theme of forgiveness as a focus.

In addition to describing how his parents met, and how both families forgave the past and moved forward, Sakamoto shares his mother’s story. Her descent into alcoholism, from which she eventually died and how, through his grandparents’ examples, he was able to work through his complicated relationship with her and move on. When Sakamoto began writing the book, he says didn’t have the theme of forgiveness as a focus.

“I thought of forgiveness in transactional terms, as an agreement, backward looking, party to party,” he said. “But in the story of my grandparents’ lives, none of that was remotely true. Forgiveness is not backward looking, it is forward looking; it is all about tomorrow. It has nothing to do with the transgression of the Japanese soldiers or the Canadian government, but everything to do with how their children’s lives were going to play out, what they were going to fill their children’s hearts with. It has nothing to do with the other party, but how you felt about the situation and how you were going to pivot away from those transgressions. My grandparents understood that the worst transgression they could commit was to pass on those transgressions to their children,” he said. “Forgiveness isn’t a big act, it’s doing it day after day, hoping that your life will get better from where it was, and for them it did. They went on to embrace Japanese-Canadian grandchildren, that’s their greatest gift to me, so soon after WWII. Right now, we’re living in a world where folks are looking for examples of hopeful lives with love or care transcending pain and trauma.”

It wasn’t until Sakamoto was finishing the book, describing the death of his mother and the birth of his first daughter that forgiveness became the central theme of the book.

“The book’s ending and my own children being born coincided with each other, and that was a very poignant moment where the two align. When your mom dies from alcoholism, it’s very painful because the whole thing is so insidious; it strikes at you at your most vulnerable, at your happiest times, so on your wedding night you’re looking out at all your friends and family, but you’re also scanning for your mom, and she’s not there. Similarly when our first daughter was born, I was handed this baby girl which is the most brilliant moment of your life, but at the same time you’re sad because her grandma’s not there. Right at that moment, in a way that was shocking to me, you realize that your heart is your child’s emotional home. Clearly, I had some rooms that needed to be cleaned up and that’s when I started to think about how did my grandparents move on from their own trauma and live with such an open heart, how did I grow up in such a emotionally clean, warm house, given what they went through and could I use their path as a guide for my own struggle to forgive and be forgiven by my mom who was no longer alive? How do you forgive someone who is dead? How do you be forgiven by someone who is dead? Those are all very difficult things to come to grips with, but my grandparents’ stories, who were fortunately alive at the time, were very illustrative to me and that’s what culminated in the book.”

During the Canada Reads promotional shoots at the CBC in Toronto, Ontario on Monday, January 29, 2018. (Photo by Peter Power)

While Sakamoto had the bones of the story when he first wrote it as a Globe and Mail article in 2011, there were challenges in writing the story as a family memoir.

“I had done enough research to do the essay,” he said. “But once I signed the book deal, I went very deep on the research and personal interviews with Ralph and Mitsue, and I saw the devil everywhere. I really pushed my grandparents in to the deepest corners of their lives at a time that was very much a time at the end of their lives. They were both extremely willing participants despite not really talking about those years in great detail before, so they were extremely generous, and they were both extremely detailed. It was shocking what my 91-year-old grandmother remembered, so I was very fortunate to have them both alive when I started to work with HarperCollins,” he said.

“When you spend time with a theme like forgiveness, at the end of the day, it’s almost impossible for it not to wash up across your own personal shores as it did in this book, and I started to write about my own personal struggle to find forgiveness in the passing of my mom; she was just a terrific mom, but she was sick. I started to write my story, but obviously it’s not just my story, it’s my brother’s story, it’s my father’s story. It’s one thing to write a kind of love letter to my grandparents who are these wonderful people who fell down and got up, but it’s another thing to weave in the story about my mother who fell down and didn’t have the strength to get up. In writing about that there are unintended casualties in the story. I spoke to them [his father and brother] about it and they were both very gracious about having faith in me to tell my story as fairly as possible,” he said.

“But it wasn’t without personal risk, I suppose. I was very cognizant of how they would perceive it and so that was in my mind while I tried to be honest and authentic. Then writing about my grandparents who I love dearly and deeply, thinking of them in situations that they were describing to me was very painful … I tried to tell the truth, I tried to tell Mitsue’s truth and I tried to tell Ralph’s truth, and I tried to tell my truth too. In telling that truth, Japan did some pretty nasty things, and I love Japan, I’ve travelled there extensively. And I love Canada; it’s the greatest place on Earth. But to really love something, whether it be a person or a country, you have to love it honestly, you have to love it warts and all. You can’t wash away anything; you can’t cover it up. If you’re not loving it honestly then you’re not loving it.”

After Sakamoto signed a contract with HarperCollins, it took him 20 months to write the book.

“The hard thing was I was working on my business, and I didn’t take a leave of absence; I’d wake up at five in the morning for 20 months and write in the morning, get my girls ready, and go to work, work, come home, edit, and then write all weekend, write all Christmases, Easters. I had to be extremely disciplined in the way I managed my time. HarperCollins was wonderful and flexible, but I did want to hit the deadlines, in large part, because both my grandparents, Mitsue and Ralph, were both still alive as I was writing and I wanted them to be alive when the story was published. Unfortunately Mitsue passed away before the book was published but she did read her draft.”

Asked when he first learned about the internment, Sakamoto replied, “I was that kid who was always interested in history and politics, so I did ask questions and prod and I did get the bones, but not details, of their story, I knew the history that my grandma’s dad had two fishing boats and he had a cod and salmon license and they lived a pretty culturally rich integrated lives in and around Steveston.”

“I did get them talking as a child, and I remember 1988—I guess I was around 10—I remember Brian Mulroney saying that the government mistreated Japanese Canadians, that ‘you are every bit a part of this country as anybody else, that we mistreated you as citizens and we are sorry for that on behalf of all Canadians.’ That was a very powerful moment in our family, and in most JC families, and I certainly applaud Art Miki and all that were part of that. I think at that point I really did start to ask a lot more questions about internment and have my grandparents talk about it, and that’s why I think in so many ways, government apologies, for admitting past actions, are important because it goes some way in ensuring that those traumas aren’t passed on to the next generation. We see that happening in front of us in so many ways, most notably with Indigenous Canadians where trauma is inherited unfortunately; it’s bequeathed to another generation. Those kind of state actions of apology can be very helpful because it opens up lines of communication; it opens up light into dark places and that’s the only way to get those dark rooms lit.”

Forgiveness was up against four other books. Sakamoto said, “I met all the other authors and they are all wonderful, terrific authors; it’s a great curated list. This year’s theme ‘books that will open your eyes,’ is interesting for me, because the themes in my book are more relevant today than when the book was published in 2014. I remember asking my grandmother, why didn’t you talk about this stuff? And she looked me dead in the eyes and said ‘Because Hate can come back.’ She didn’t want to give voice to it. At the time I chuckled; I laughed at the notion that the world wasn’t progressing in 2010—Barack was in the White House, the world, while not perfect by any means, but I took progress for granted. But look where we are today, you can’t turn on the CBC or CNN or the Globe and Mail and not see some semblance of racial intolerance, state-lead action that harkens back to those injurious years. There are a lot of things that are eye-opening in my grandparents’ story, not least which is, number one, hate always comes wrapped in the flag, it’s the oldest trick in the book,” he said.

“Two, you never just end up in the basement, there’s always a little step, then another step: my grandparents had a curfew, and then they had to get carded, and then they had to give up their radios and they lost all their possessions and then they ended up in a chicken coop in southern Alberta; it happens step, by step, by step, so we have to remain cognizant and keep our eyes peeled.”

“One of the great things that came out of Canada Reads is, whatever the outcome, befriending and being befriended by Jeanne Beker. She’s absolutely terrific,” he said. “She’s a really wonderful spirit. She’s the daughter of Holocaust survivors so she intimately understands the themes that are explored in the book and also had parents that were able to, by sheer strength and will, overcome the atrocities that Jewish people faced in Europe and went on to lead a productive, hopeful life. So she gets it, so Forgiveness is in very good hands in the Canada Reads project.”

He added, “For me, being able to tell their stories; their lives were so remarkable. Both of them couldn’t believe that anyone, especially a big international publishing house would be interested in their lives, but their lives touch very universal themes about resilience and getting back up, trying your damnedest to live everyday.”

To watch the full debates and for the titles of the other books, please visit: www.cbc.ca/books/canadareads.

***

20 Apr 2018

20 Apr 2018

Posted by Karri Yano

Posted by Karri Yano

1 Comment

What an excellent article about Mark’s book. Well done to Mark and well done Kelly Fleck for capturing the essence of what we can learn from Mark’s story.