Staff associate Jane Kurahara, President and Executive Director Carole Hayashino, staff associate Betsy Young and Education Specialist Derrick Iwata in the resource center, the largest of its kind in Hawaii, at the Japanese Cultural Center of Hawaii.

HONOLULU — Japanese culture in Hawaii is different than any other place in the world. Japanese Hawaiian culture has a long history leading back to 1868. As well, Japanese make up 16.7 per cent of the population in Hawaii, according to U.S. Census Bureau, a larger population than Filipinos at 14.1 per cent or Chinese at 4.7 per cent.

Comparatively, the entire Japanese population in Canada is 0.3 per cent.

There are ramen or sushi shops on every city street and almost every sign is written in English with Japanese below. Even the airport in the capital of Honolulu is named after a Japanese Hawaiian, Daniel K. Inouye, a state senator and Second World War hero.

In 2015, 1.5 million Japanese tourists visited Hawaii, and there is a bustling tourism community directed specifically to Japanese tourists.

With nearly 150 years of history, and the large population, Japanese culture has become a part of Hawaiian culture. At the epicenter of this vibrant community is the Japanese Cultural Center of Hawaii.

“Don’t you see and feel Japanese culture embedded in Hawaii? I think it is truly integrated,” says President and Executive Director Carole Hayashino. “We often say that many of the Japanese traditions and culture have really blended and become local Hawaiian culture.”

“Don’t you see and feel Japanese culture embedded in Hawaii? I think it is truly integrated,” says President and Executive Director Carole Hayashino. “We often say that many of the Japanese traditions and culture have really blended and become local Hawaiian culture.”

The cultural center sets out to preserve the diverse culture that has come out of that and to share that culture with the younger generations.

The center does this through cultural classes, festivals and bazaars, as well as facilities like a dojo, ballroom, museum, education center and resource center.

Japanese Hawaiians can learn more about their own personal history by using the Takioka Heritage Resource Centre. The largest resource centre of its kind in Hawaii, it contains over 5,000 books, in both Japanese and English.

Included in the resource center are diaries, letters, manuscripts, oral history transcripts and historical photos.

Resource staff have helped visitors do genealogical research, translate family registries and even consult on Japanese names, helping visitors learn about their given Japanese middle names or pick names with significant meanings for their children.

People come into the resource center looking to learn about their own history, says Hayashino.

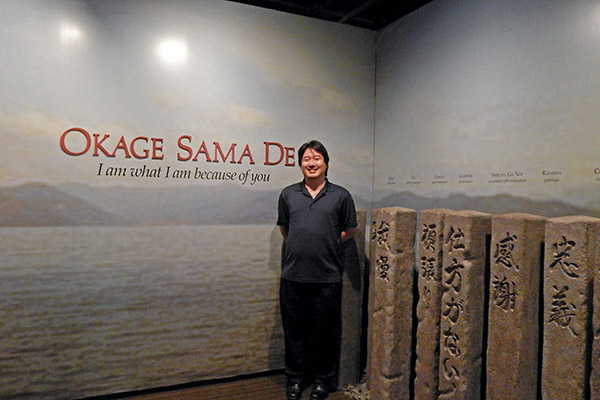

A major highlight of the center is it’s permanent exhibition, entitled, Okage Sama De: I am what I am because of you.

The exhibit opens on a wooden plank floor, with floor-to-ceiling images of the sea and the Hawaiian islands, to create the feeling of the first Japanese immigrants stepping off the boat and into Hawaii.

The exhibit begins with the first Japanese immigrants that arrived in Hawaii in 1868, as a way to build allies between the two countries (Hawaii was not yet part of the United States).

The exhibit documents the Japanese men who immigrated to Hawaii to work on the sugar cane plantations. Following the men, picture brides came to Hawaii. It was part of an effort to keep the Japanese men in Hawaii, working on the sugar cane plantations. Eventually having children, the Japanese immigrants would stay in Hawaii.

“For the sake of the children, they gave up on dreams of going home,” says Derrick Iwata, education specialist at the center.

The exhibit documents the growth of the Japanese community in Hawaii with models of traditional homes, plantation schools, and an entire mock street with Japanese stores, groceries and churches.

The exhibit closes off with an overview of the postwar Japanese Hawaiian population. Japanese Hawaiians were able to take jobs in all types of fields, including running for political office. In 1954, 10 out of 15 senate seats were filled by Japanese Hawaiians. This drives home the statement at the beginning of the exhibit, Okage sama de, ‘I am what I am because of you.’ The sacrifices and hardships the first generations made, lead to the Japanese Hawaiian community that thrives now, says Iwata.

The immersive exhibit is definitely a shining spot for the centre, and was created by Jane Komeiji, Tom Klobe and Momi Cazimero in 1995. The exhibit went through a renovation in 2012 to become what it is today.

The centre has created a high school curriculum that was sent to every high school in Hawaii. The curriculum is filled with information and guidelines on how teachers can teach their students about Japanese Hawaiian history.

Each year thousands of grade school children visit the center to learn about Japanese Hawaiian history, says Iwata.

Depending on the ages of the students, they will different aspects of Japanese Hawaiian culture. Younger students learn about Japanese culture and games. Older students learn about Japanese immigration to Hawaii, men working in the sugar cane fields and the picture brides that followed, says Iwata.

It is important that the cultural center acts as a resource for schools to teach children about Japanese Hawaiian history, says Iwata. In the past, the center has raised funds for bus transportation to get students to the cultural center.

With Japanese culture and people all around Hawaii, the Japanese Cultural Center of Hawaii is at the center of it all, preserving that culture and sharing that history.

“People don’t think about Japanese in Hawaii. We all have stories, no matter whether they are in the United States, Canada or Hawaii,” says Iwata.

***

Japanese Hawaiian Internment:

The history of Japanese Hawaiian internment is much different than that of the Japanese Canadian experience or even the Japanese American experience in places like California, Oregon or Washington.

The attack on the United States naval base at Pearl Harbor in Hawaii Territory sent shock waves around the world, changing the lives of Japanese Canadians and Americans.

As a result, on Feb. 19, 1942, President Franklin D. Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066, leading to the incarceration of over 120,000 Japanese Americans, many American born, into internment camps.

Internment posed a problem in Hawaii. Over one third of the Hawaiian population came from Japanese decent, and made up much of the labour force. Interning 40 per cent of the population on an island had not only logistical issues, but would lead to economic turmoil in Hawaii.

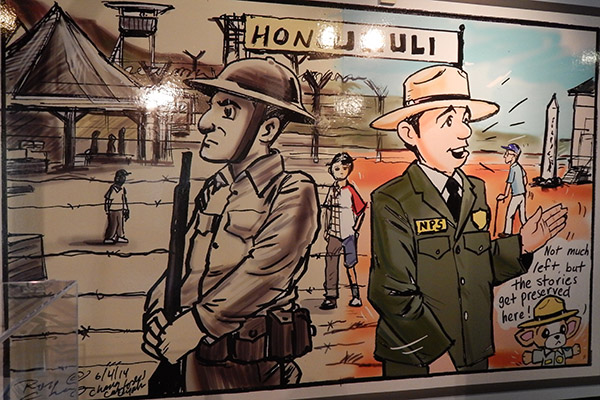

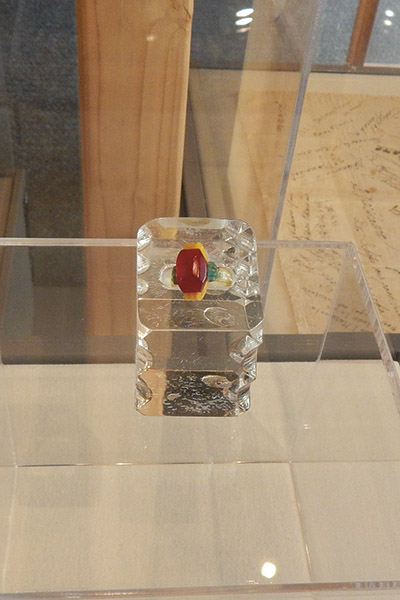

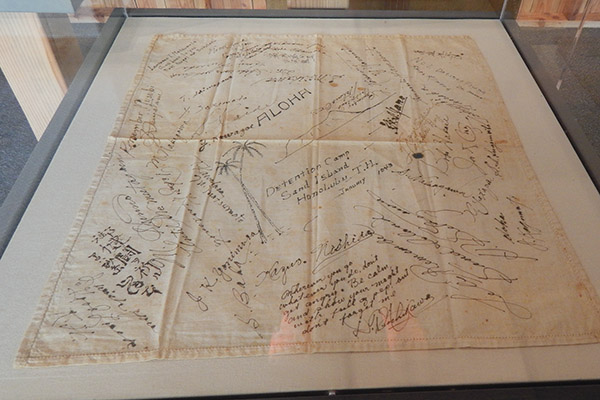

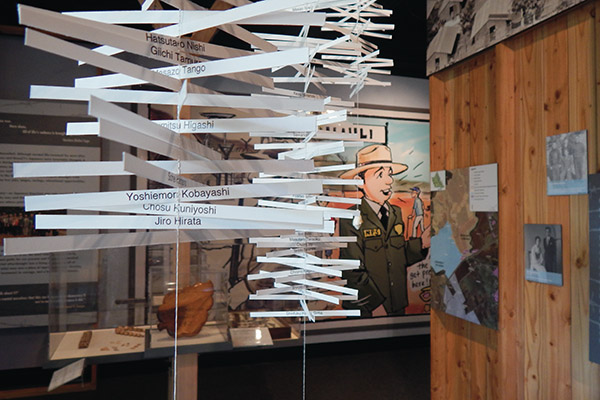

Instead, under martial law, 2,269 community leaders were arrested, interrogated and detained. These leaders included Buddhist and Shinto priests, language teachers, fishermen and journalists. No one was ever charged. They were sent to detention camps across Hawaii, including Honouliuli, which you can read about in the slideshow below.

29 Jun 2017

29 Jun 2017

Posted by Kelly Fleck

Posted by Kelly Fleck

1 Comment

[…] The Japanese spirt of aloha: Japanese Cultural Center of Hawaii preserves Japanese culture […]