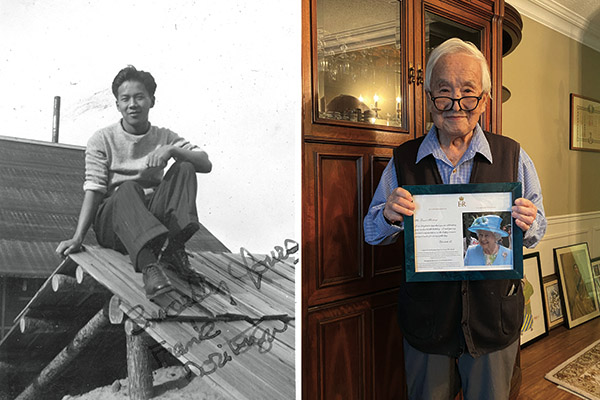

Left: A 19-year-old Frank Moritsugu sitting on the roof of a Yard Creek camp shack in 1943. Repository: JCCC. Collection: Dawn Miike Collection. Accession Number: 2014.02.01.09. Right: Current day Frank holding a letter with birthday wishes from the Queen for his 100th birthday.

TORONTO — There are not many centenarian journalists, and even fewer who continue to actively and regularly write, but Frank Moritsugu is the exception. Moritsugu, a Nisei war veteran, esteemed journalist, and beloved Nikkei Voice columnist, celebrated his 100th birthday on Dec. 4.

“Becoming 100 years old is very strange. I’m very happy I did it, but it’s not something I ever dreamed of,” Moritsugu tells Nikkei Voice during an interview in his Etobicoke condo.

Moritsugu’s journalism career has spanned over eight decades—he was still a teenager when he was first hired by The New Canadian editor Tom Shoyama. Moritsugu was among the first Japanese Canadian journalists to write for mainstream publications. Along with The New Canadian and Nikkei Voice, his career includes Maclean’s, Canadian Homes & Gardens, CBC, the Toronto Star, and the Montreal Star.

But a career in journalism was not always something Moritsugu envisioned for himself. While he loved writing in school and working for The New Canadian, he could never imagine becoming a journalist—Japanese Canadians did not work for mainstream newspapers and magazines.

“Back in B.C. when we were growing up, you never saw a Japanese name in the bylines of any newspapers or anything like that,” says Moritsugu.

Born in Port Alice, B.C., and raised in Vancouver’s Kitsilano neighbourhood, Moritsugu is the oldest of eight children. Reflecting on his life and formative years, a big part of what led Moritsugu down this career path was his parents and the pressure they put on him to be the best he could be.

Moritsugu’s parents immigrated from Tottori, Japan. His mother, Shizuko, completed her high school education in Tokyo, something many women in her time did not have the opportunity to do. She returned to Tottori to work as a school teacher until she married Masaharu Moritsugu on Christmas Day in 1921 and immigrated to Canada. Masaharu “Frank” immigrated to Canada a few years earlier, working as the Japanese foreman in Port Alice.

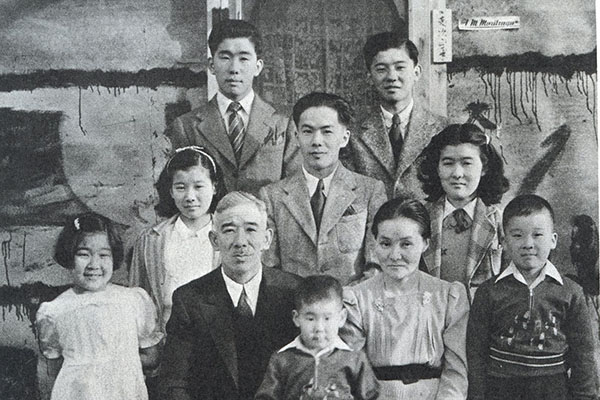

The Moritsugu family during a temporary reunion in Tashme. Top row (left to right): Ken and Harvey. Centre row: June, Frank, and Eileen. Front row: Joyce, father Frank Masaharu, mother Shizuko, and Henry. Ted, the youngest, stands in front between his parents. Photo courtesy: Frank Moritsugu.

When it was time for a four-year-old Moritsugu to start kindergarten at the Japanese United Church near the Powell Street grounds, his mother wanted him to be ready. She taught him the Japanese and English alphabets, Japan’s national anthem, and The Maple Leaf Forever (O’Canada was not yet the national anthem). There were always books, magazines, and newspapers in their Kitsilano home, and Japanese magazines brought over on steamships so he could practice reading in Japanese.

“I was a very serious bookworm—I still am—and I started as a young kid, and the majority of my siblings are exactly like that,” says Moritsugu. “With a mother like that, she had me practicing reading at home when I was still in kindergarten… I’m the oldest, as it turned out eventually, of eight kids, [my parents were] expecting me to be a good student who is always leading the best in class from kindergarten on to public school.”

In high school, Moritsugu loved writing and discovered he also enjoyed editing his classmates’ work and finding ways to make it better. In grade 12, Moritsugu was elected editor-in-chief—over his Caucasian peers—of the school newspaper, Kitsilano High School Life. But, despite doing well in school, attending university was not an option after finishing high school.

“Because of the depression era and I was the oldest of eight kids, there was no way—even though I did reasonably well in high school—for me to go to university, the family couldn’t afford it,” says Moritsugu.

But life as Moritsugu knew it was about to change forever. In 1942, when coastal-living Japanese Canadians were forcibly uprooted, dispossessed, and interned, Moritsugu was separated from the rest of his family and sent to Yard Creek, one of six highway work camps between Sicamous and Revelstoke, later joined by his brother, Ken.

Moritsugu remained in Yard Creek until he received a phone call from editor Tom Shoyama, asking if he would join The New Canadian again, this time in the Kaslo internment camp, as assistant English editor. After seven months in Kaslo, Moritsugu reunited with his family, who had relocated to St. Thomas, Ont., working on the 100-acre farm of former Ontario premier Mitch Hepburn alongside two other Japanese Canadian families.

In 1945, the ban against Japanese Canadians enlisting in the Army was lifted. The British Army desperately needed Japanese language interpreter-translators, and Canada had the largest Nikkei population in the Commonwealth. Despite his parents losing everything they had worked for during the war, Moritsugu enlisted, wanting to prove that Japanese Canadians were 100 per cent Canadians.

Shortly after enlisting, when the ban on Japanese Canadians joining the Army was lifted, Frank’s mother told him to get his photo taken in uniform. Photo courtesy: Frank Moritsugu.

Moritsugu served in Southeast Asia as a Japanese-language interpreter-translator, later attaining the rank of sergeant in the Canadian Army Intelligence Corps, attached to British counter-intelligence forces.

But discrimination did not end just because Moritsugu became a soldier. Moritsugu recalls his scariest wartime experience occurred while waiting to return home in a camp near Bombay (Mumbai), India. After spending the evening playing bridge with fellow Nisei soldiers, the men returned to the barracks. There were not enough beds in the bunkhouse, so Moritsugu and another Nisei soldier, Elmer Oike, stayed in another on their own.

As they fell asleep, they heard four British soldiers enter the barracks. The men were agitated and drunk, and one man began rummaging through his bag. When his comrades asked what he was doing, he angrily replied with profanity and slurs, getting his gun because he knew the Japanese were here. Usually, soldiers hand in their rifles on base to the quartermaster, but those in the special forces, like these men, often had pistols in their kit bags, explains Moritsugu.

“He’s rummaging around, trying to get his weapon. Now imagine, Elmer and I can’t communicate with each other. All we had to protect ourselves is a bloody mosquito net,” says Moritsugu.

Suddenly, there was silence. The man, intoxicated, had passed out. The other three men went to bed, but Moritsugu and Elmer lay awake in the bunks for hours afterward. The next morning Elmer reported the incident to the officers’ building, and the men were gone by the time they returned after breakfast.

“Somebody asked were you ever in any danger [during the war]. That was among all that time that we went ahead and with all the other stuff around, the only time that really scared me to death,” says Moritsugu.

After completing his service, Moritsugu was eligible for veterans’ benefits, which included a university education. Moritsugu applied to the Ontario College of Arts and Design to become a commercial artist.

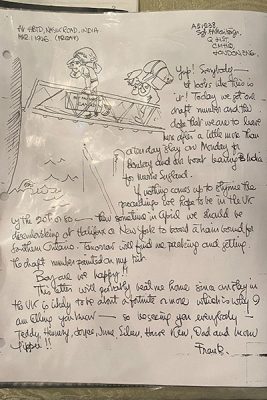

A letter written by Frank to his mother, letting her know he was returning to home after completing his Army service. Included in the letter are some of Frank’s illustrations. Photo credit: Kelly Fleck.

With the influx of returning soldiers, Moritsugu had to wait a year to attend school, so he returned to St. Thomas, working on the farm with his family. After the harvest season, he visited some friends in Toronto, including Dr. Irene Uchida, a geneticist, educator, and fellow writer at The New Canadian. Dr. Uchida encouraged Moritsugu to meet with B.K. Sandwell, editor of Saturday Night, Canada’s oldest general culture magazine.

A very English man, who looked “like he came out of a Charles Dickens novel,” muses Moritsugu, Sandwell was one of the journalists who vocally opposed the campaign to repatriate Japanese Canadians to Japan after the war. During their meeting, Sandwell asked why there were Japanese Canadians who remained in B.C. after the war, instead of moving East across Canada. Moritsugu listed a couple of reasons. Sandwell replied by asking Moritsugu to put an article together for him.

“As I walked out of his office in downtown Toronto, I thought, I’m being asked to write a magazine article. I’ve never written a magazine article in my life,” says Moritsugu.

Moritsugu left Sandwell’s office and went straight to a bookstore, picking up books on magazine writing. He then got to work, staying in Toronto a few extra days at a fellow ex-Kitsilano family’s home, writing his article for Sandwell.

After filing his story, Moritsugu began working for The New Canadian again, now based in Winnipeg. When he received a note from Sandwell saying his article was published, he rushed out to get a copy. And there it was, his article in a major Canadian publication.

“It was by Frank Moritsugu. Wow, I thought, I don’t have to go to commercial art, I can actually write, and that was something that never happened back in B.C.,” says Moritsugu.

With the advice of Sandwell, Moritsugu enrolled at the University of Toronto, taking a four-year program in political science and economics to become a journalist. In his first year, he started writing for the university’s newspaper, The Varsity. He was already familiar with newsroom operations after The New Canadian. In his third year, he was elected editor-in-chief, becoming the newspaper’s first Japanese Canadian editor.

That same year, Moritsugu won a major editorial award in the annual Canadian University Press competition, which helped set him on his journalism career after university.

“As it happened, one of the judges of the competition was Ralph Allen, the editor of Maclean’s magazine,” says Moritsugu. “Ralph Allen and everybody liked it and gave me the award, but not only that, he followed up by wanting to know when I was going to finish university.”

While Moritsugu finished his last year of university, he would come into the Maclean’s office once a week and work as an assistant copyeditor. After graduating, he started working at Maclean’s full time.

Over his career, Moritsugu worked for many mainstream media outlets, including CBC Radio, Canadian Homes & Gardens, and the Toronto Star. His previous work as a translator-interpreter in the Army came in handy for pre-1962 Tokyo Olympic coverage, writing about postwar Japan. Before retiring, Moritsugu was an instructor at Centennial College.

Frank Moritsugu with family after receiving the Order of the Rising Sun, Gold and Silver Rays on Jan. 11. Frank and his wife Betty have been married for nearly 40 years, and they have six children, many grandchildren, and even a few great grandchildren. Photo credit: Kelly Fleck.

In his retirement, Moritsugu continued to write, including for this publication. Many in the community know Moritsugu from his talks about his wartime experience at schools, conferences, and Remembrance Day ceremonies, among many other events.

When his youngest daughter’s children were in high school, she found the history curriculum lacked its history of Japanese Canadians, and encouraged Moritsugu to speak to their classes.

“Apparently, in the grade 10 Canadian history textbook, there are two little paragraphs about something happening to us. That was so inadequate,” says Moritsugu.

It felt important to tell these stories and ensure they are not forgotten and do not happen again. Each talk led to another, and Moritsugu continued to speak at schools well into his 90s. But in the last few years, the talks were becoming quite strenuous. The pandemic ended his school talks.

Now, Moritsugu is creating a resource to share with the Japanese Canadian Cultural Centre, Nikkei National Museum, schools, and anyone else interested, so they can learn about Moritsugu’s wartime experiences from him firsthand when he can’t be there in person.

“Here I am, maybe the last surviving Second World War veteran. There’s so few of us who went through all that, who are active to do it, and [can] speak publicly,” says Moritsugu. “It goes right back to the kind of person my parents raised and the kind of people they were.”

Frank Moritsugu (centre) during a Remembrance Day ceremony at the Japanese Canadian Cultural Centre on Nov. 4, 2022. Photo credit: Yosh Inouye.

***

17 Jan 2023

17 Jan 2023

Posted by Kelly Fleck

Posted by Kelly Fleck

1 Comment

[…] the Toronto Star, which gets a special call out in the show. Her father, retired Star journalist Frank Moritsugu (and long-time Nikkei Voice contributor), was on assignment to interview a successful French […]