Artist Kellen Hatanaka explores historical and contemporary issues of race, xenophobia, and bias in sport. Left: Home, 2020, by Kellen Hatanaka. Right: Artist Kellen Hatanaka. Photo credit: Kiersten Hatanaka.

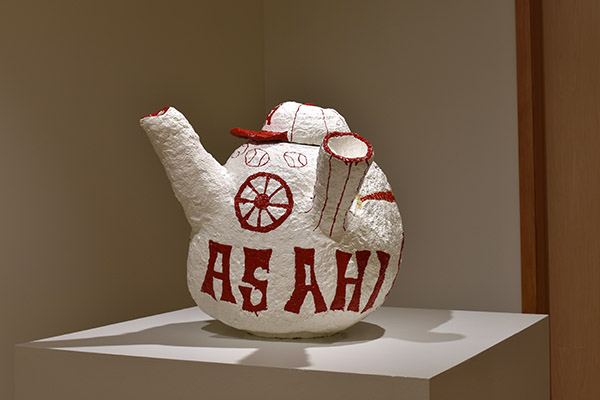

STRATFORD — In artist Kellen Hatanaka‘s installation SAFE | HOME at the Nikkei National Museum & Cultural Centre is sculptures of sports memorabilia for the legendary Asahi Baseball Team. A teapot with the team’s colours and ASAHI name emblazoned across the front. An action figure with dark hair under a red striped baseball cap. An Asahi ’93 Championships commemorative bottle opener.

But of course, the Vancouver Asahi never won a 1993 championship. The club disbanded in 1941 when Japanese Canadians were dispossessed and interned during the Second World War.

Instead, SAFE | HOME asks what could have been if the Asahi were never forced to disband. Through painting and sculpture, Hatanaka uses the rise and fall of the Asahi to explore how these significant losses have affected generations of Japanese Canadians. Through the lens of the historic Asahi team, the exhibit also explores issues of race, xenophobia, representation, and implicit bias relevant in sport and society today.

Pride of Powell Street (Backs), 2021. Photos courtesy of the artist.

“I wanted to use the team as a way to discuss issues that are contemporary, as well as, historical and not just rooted in a historical or illustrative retelling, using [the Asahi] as a metaphor for what happened to the Japanese Canadian community,” Hatanaka tells Nikkei Voice in an interview. “One of the big questions I had was, what would’ve been if not for the internment? How do you conceptualize [that], because there is no answer, but it is an opportunity to dream and consider what those things might have been.”

Hatanaka is a visual artist from Toronto, now based in Stratford, Ont., whose vibrant figurative work tackles issues of identity, heritage, tradition, and the Asian Canadian experience. An illustrator who has worked with brands and publications like Nike, The Wall Street Journal, and The Drake Hotel, Hatanaka is a Governor General Award recipient alongside author Jon-Erik Lappano for their children’s book, Tokyo Digs a Garden.

SAFE | HOME does not replicate any specific player or moment in history. Instead, the Asahi provide an anchor to explore themes of loss, identity, and culture in the Japanese Canadian community. These dark themes are juxtaposed with bright colours and playful figures, as the work also celebrates the team as a source of pride and joy for the community. During their prime, the Asahi won multiple league titles and filled the stands with both Japanese and non-Japanese fans. The team’s success helped build bridges between the Japanese Canadian and wider-Vancouver community in the 1920s and 30s.

“I think about how much the team meant to the community—because that was pretty special to learn about—it became very clear through how people spoke about them,” says Hatanaka. “For some people, that was the only light because life was hard, but they had this one respite, so I felt they needed to be shown in that light.”

Pride of Powell Street (Fronts), 2021.

When visitors enter the exhibit, they are greeted by Pride of Powell Street, three massive panels depicting three Asahi players. Intentional in size, the work emphasizes that while the players were physically smaller, they had a larger-than-life image in the community.

In Line Up, six images of three players on bright, colourful backgrounds look like baseball cards lined up next together. But the way each player is posed, in front and side profile, also looks like a lineup of mug shots, recalling the label of enemy aliens and the incarceration of Japanese Canadians. Carefully and intentionally, Hatanaka balances bright images with the dark undertones just below the surface.

Line Up, 2021.

“I thought a lot about the way my grandma would talk to us about internment, which was pretty guarded and sort of surface level,” says Hatanaka.

Like many other Japanese Canadians, his grandmother spoke about the internment with the attitude of shikata ga nai, it can’t be helped. But as Hatanaka grew older and began to research the internment, he realized the history was a lot darker than she let off.

“I felt like I had to be angry about that for her. But that kind of resiliency is pretty amazing, and even though [Japanese Canadians] were living in these horrible circumstances, there were moments of joy, even in the camps. The fact that people could find joy in that experience is pretty inspiring as well.”

A reoccurring image throughout the exhibit is a Japanese teapot, which Hatanaka felt symbolized the way his grandmother spoke about the internment. On the outside, she was calm and stoic, but like a teapot, there is this raging, boiling water inside, and only the little bit of steam that escapes from the small spout indicates that there is something more inside. Like all of the images he paints, the teapot carries a deeper meaning for Hatanaka, based on a real teapot he inherited from his grandmother.

“I just really loved this particular teapot that she passed on to me,” says Hatanaka. “All of her objects are my last ties to her and one of the closest bonds I have to my Japanese heritage in general.”

The teapot also appears in the exhibit in sculpture form. Hatanaka’s sculptures are made of paper mache, layers of soft and malleable paper pulp applied to a wire frame. As the pulp dries, it takes on an organic shape, capturing the duality of dealing with memory, an archive of the past that is not exact, and imagining a future that never happened for the Asahi.

Untitled (Tea Pot), 2021.

Paper pulp is a very wet material, and just a quarter-inch of pulp equals hundreds of sheets of paper, so it takes a long time to dry. In the summer, Hatanaka would bring the sculptures home from his studio to dry outside. Hatanaka’s son, three at the time, was fascinated by the sculptures and wanted to help. Together, Hatanaka and his son formed the pulp into the teapot sculpture that now sits in the exhibit.

“That was a key focus [of SAFE | HOME] as well, what are the intergenerational effects, going through my grandparents, my father, and me? What is the impact on my children, and how does it continue on and on,” says Hatanaka.

The exhibit also explores themes of identity and racism in contemporary sport. For Hatanaka, both through sport and the pandemic, it has become quite apparent that anti-Asian sentiments are still prevalent in North America.

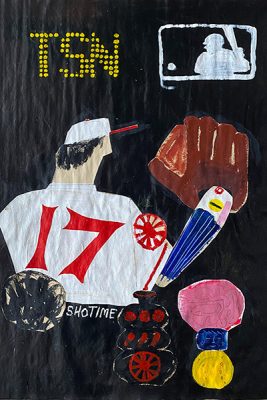

Shotime, 2021.

One way Hatanaka explores that is through Los Angeles Angels’ Shohei Ohtani. A large and powerful player, Ohtani’s achievements have been compared to baseball legend Babe Ruth, but Ohtani is yet to receive that recognition and faces regular derogatory comments about his ethnicity.

“I think the thing that is different about [Ohtani] is that he challenged the sort of person that people hold up as almost the pinnacle of baseball, which happens to be a white male player,” says Hatanaka. “It’s interesting that this one player seems to be throwing a wrench in the social narratives.”

While there have been many Japanese baseball stars in Major League Baseball, like Ichiro Suzuki, while inspiring players, often do not challenge the narrative of what an Asian player should look like, says Hatanaka. Suzuki, who is small in stature, fast on his feet, and known to work extremely hard, fits the narrative of what sports fans feel an East Asian player should be.

Stories like Ohtani and the Asahi Baseball Team continue to inspire Hatanaka. Exploring these sports stories through contemporary art becomes a way to challenge the existing narratives of Asians in sports and empower Asian youth to feel like they belong in these spaces.

“That’s where the original kind of work around that came from, and I keep finding more and more stories that are compelling to share. I think that’s part of what I want to do, is share these stories and find a way to do it that fits within contemporary art,” says Hatanaka.

“If there are figurative works at contemporary art museums, and it happens to be an Asian American athlete, I think that does a lot for representation and changing people’s perceptions. That’s kind of the ultimate goal, is being able to pull [the Asian figure] into a space where they can also live within contemporary art.”

***

SAFE | HOME will be at the Nikkei National Museum until April 30, 2022. Learn more here.

Learn more about Kellen Hatanaka at www.kellenhatanaka.com.

16 Mar 2022

16 Mar 2022

Posted by Kelly Fleck

Posted by Kelly Fleck